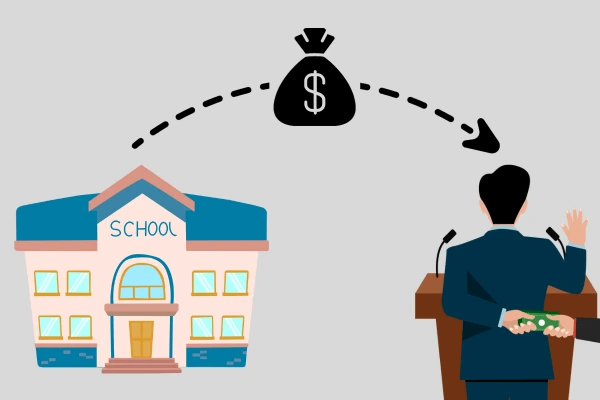

Inurement is just another word for benefit. Private inurement is legal jargon for when a nonprofit board member or insider uses their control over the nonprofit to obtain personal benefits, at the expense of the nonprofit’s mission.

Example 1: Nonprofit pays above-market rent to board members

Texas Trade School was an educational nonprofit. Five members of the board of directors received above-market-rate rental income from the nonprofit. This was private inurement.

Texas Trade School v. Commissioner, 30 T.C. 642, aff’d. 272 F.2d 168 (5th Cir. 1959)

Example 2: Zero-interest loans to a board members’ family

A nonprofit private unaccredited law school was operated by two brothers, Theo and Martin Fenster, and members of their family. Martin used his control of the organization to provide his family with an interest-free unsecured loan to purchase a home and furnish it. That was private inurement.

John Marshall Law School and John Marshall University v. United States, 81-2 USTC 9514 (Ct. Cl. 1981)

The concept or private inurement is important because it jeopardizes a nonprofit’s tax-exempt status with the IRS. Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code provides an exemption from federal income tax for organizations that are “organized and operated exclusively” for religious, educational, or charitable purposes, but ONLY as long as “no part of the net income [of the organization] inures to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual.”

Essentially, a nonprofit must be exclusively formed and operated to benefit the public, not specific individuals, in order to qualify for the 501(c)(3) income tax exemption. However, the real world is a messy place. According to an IRS text on the topic, “in the charitable area, some private benefit may be unavoidable. The trick is to know when enough is enough.”

Treasury Regulations describe the anti-inurement requirement in more detail as follows:

“An organization is not operated exclusively for one or more exempt purposes if its net earnings inure in whole or in part to the benefit of private shareholders or individuals… [If an organization] fails to [be operated exclusively for one or more exempt purposes], it is not exempt [from federal income tax]…The words ‘private shareholder or individual’ in section 501 refer to persons having a personal or private interest in the activities of the organization.”

26 CFR 1.501(c)(3)-1 subparts (a) and (c)

Courts have focused on the word “private” in the above excerpts. “Private” is held to mean the antonym of “public”. In other words, a private individual is distinguished from the general public. Of course, any individual who receives goods or services from a charity derives benefit. But as long as that person received that benefit just for being a member of the public, rather than receiving a special benefit only available to insiders, then the benefit doesn’t constitute private inurement.

Example 3: Fee waiver for board members

A nonprofit art gallery allows gallery members to exhibit their artwork for a fee. However, the nonprofit’s board members can exhibit their artwork without cost. That is private inurement because although artwork exhibition is a benefit the nonprofit offers publicly to all its members, free artwork exhibition is not.

In other words, the private inurement rule restricts the ROLE in which a person receives benefits more than it restricts WHO can receive benefits. If a board member receives a benefit that the nonprofit also offers publicly, then that probably isn’t private inurement. It is the CAPACITY in which an individual derives financial benefit that will determine whether prohibited inurement exists.

We can summarize this with two core principles:

- An individual is not entitled to unjustly enrich himself at the organization’s expense, and

- Benefits directed to an individual as a member of a charitable class do not constitute unjust enrichment.

The second principle says that a member of a nonprofit hospital’s governing board can still be admitted to that hospital. The first principle says that such a board member cannot be billed at a discounted rate for their hospitalization. The first principle also prohibits a special nonprofit hospital from being formed with the intention of funneling 30% of the hospital’s resources towards a member of the nonprofit’s board who has a chronic illness.

Example 4: Dissolution rights to previously donated property

A husband and wife couple founded a nonprofit, the Religious Society of Families. One of the religious tenets of the nonprofit was that married couples had a duty as stewards of the earth which could be fulfilled by caring for and preserving a plot of land. The couple donated 50 acres of land to the nonprofit and made good faith efforts to attract other couples to occupy portions of the property. However, those efforts were unsuccessful. Because of that, the couple who donated the land still had 100% of the control of the organization, including the right to decide to dissolve the organization and the right to decide what would happen to the organization’s assets if it was dissolved. The IRS challenged the tax-deductability of the initial 50 acre donation at this point, and court reiterated that “the burden of proof is, of course, upon the petitioners to show entitlement to the charitable contribution deduction. They must show, inter alia, that their organization was operated exclusively for religious purposes.”

In the court’s final decision, they concluded “we are convinced of the sincerity of petitioners’ convictions… [but the problem is that] upon dissolution of the organization (an occurrence wholly within petitioners’ control) its assets will revert to the petitioners [or] at the least they will have ultimate authority over their disposition. Even though they may intend at this time to distribute the assets to some other exempt organization, there is not the irrevocable commitment which allows us to find it was ‘operated exclusively for religious purposes’ [or that] ‘no part of the net earnings [inures] to the benefit of any private [individual].”

Calvin K. Of Oakknoll v. Commissioner, 69 T.C. 770 (1979), aff’d by unpublished order (2nd Cir. 1979)

Contractual & Financial Complications

There is no prohibition against a 501(c)(3) organization hiring (for pay, as an employee, contractor, or otherwise) its founders, members, or officers. However, any transaction between a 501(c)(3) organization and a private individual in which the individual appears to receive a disproportionate share of the benefits of the exchange relative to the charity presents an inurement issue. Such transactions may include assignments of income, compensation arrangements, sales or exchanges of property, commissions, rental arrangements, gifts with retained interests, and contracts to provide goods or services to the organization.

Notably, modern compensation arrangements often include a variety of benefits in addition to salary. The general rule is that if the arrangements are indistinguishable from ordinary prudent business practices in comparable circumstances, a fair exchange of benefits is presumed and inurement will not be found. If the transactions depart from that standard to the benefit of an individual, then you have inurement.

For example, OpenAI has interpreted that guidance to mean that since equity is a standard part of tech startup compensation, then it is okay for high level OpenAI nonprofit employees to be compensated with equity in the for-profit subsidiary OpenAI, LP.

A somewhat comparable case from the past is Rul. 69-383, 1969-2 C.B. 113. In that situation, a revenue ruling determined that inurement did not occur. The situation involved a tax exempt hospital entering into a contract with a radiologist after arm’s-length negotiations. The contract specified that the radiologist would be compensated by receiving a percentage of the gross receipts of the radiology department. The revenue ruling concluded that the contract did not jeopardize the hospital’s 501(c)(3) status. In support of that conclusion, several relevant facts were cited:

- The contract was negotiated on an arm’s-length basis.

- The radiologist did not control the hospital.

- The amount received by the radiologist under the contract was reasonable in terms of the responsibilities and duties assumed.

- The amount received by the radiologist under the contract was not excessive when compared to the amounts received by other radiologists in comparable circumstances.

Of course sometimes, people try to disguise inurement as reasonable compensation. For instance, in the case “John Marshall Law School and John Marshall University v. United States (81-2 USTC 9514)”, a private, unaccredited, law school and college were operated by two brothers, Theo and Martin Fenster, and members of their families. The IRS revoked the 501(c)(3) exemption of both the law school and the college on the grounds that part of the net earnings of the organizations inured to the benefit of private shareholders or individuals. The Court opened its discussion of the case by noting that:

“The term ‘net earnings’… has been construed to permit an organization to incur ordinary and necessary expenses in the course of its operations without losing its tax-exempt status…The issue, therefore, is whether or not the expenditures JMLS paid to or on behalf of the Fenster family were ordinary and necessary to JMLS operations.”

The Court then went on to detail a series of interest-free, unsecured loans used by the Fensters to purchase a home and furnish it, noncompetitive scholarships granted to the Fenster children, and the payment of nonbusiness expenses for travel, health spa memberships, and entertainment of Fenster family members.

Other case examples of inurement include:

- An organization paying someone excessive rent (Texas Trade School v. Commissioner, 30 T.C. 642 — 1959)

- An organization receiving less than fair market value as part of a sale or exchange of property (Sonora Community Hospital v. Commissioner, 46 T.C. 519 — 1966)

- An organization providing an inadequately secured loan to a private person (Lowry Hospital Association v. Commissioner, 66 T.C. 850 — 1976)

Another example of particular relevance to OpenAI is the case “People of God Community v. Commissioner” where the court decided that a percentage-of-earnings-share compensation arrangement for a minister was unreasonable compensation because there was no upper limit on the amount of compensation that the minister could receive. This is why OpenAI’s for-profit subsidiary caps investor returns at 100-times the initial investment.

Private Inurement vs Unrelated Business Income

Private inurement and unrelated business income are both situations that can negatively affect nonprofits. However, the two are very different. Private inurement refers to an inappropriate benefit that a nonprofit board member or insider receives from the nonprofit, at the expense of the nonprofit’s mission. On the other hand, unrelated business income is income that a nonprofit receives which is unrelated to the nonprofit’s mission and is therefore subject to taxation.