“Imagine if you bought $100,000 of bonds and then the bond market dropped by 20%. If you were a normal, rational person, you would say your portfolio is now worth $80,000. However, if you were a bank, you would say your portfolio is still worth $100,000.”

First Republic Bank Stock Price

First Republic Bank had a problem long before its stock dropped over 81% in 2 weeks, and that problem was hidden in plain sight for anyone willing to read through the tedious “notes to consolidated financial statements” in the company’s 2022 annual report.

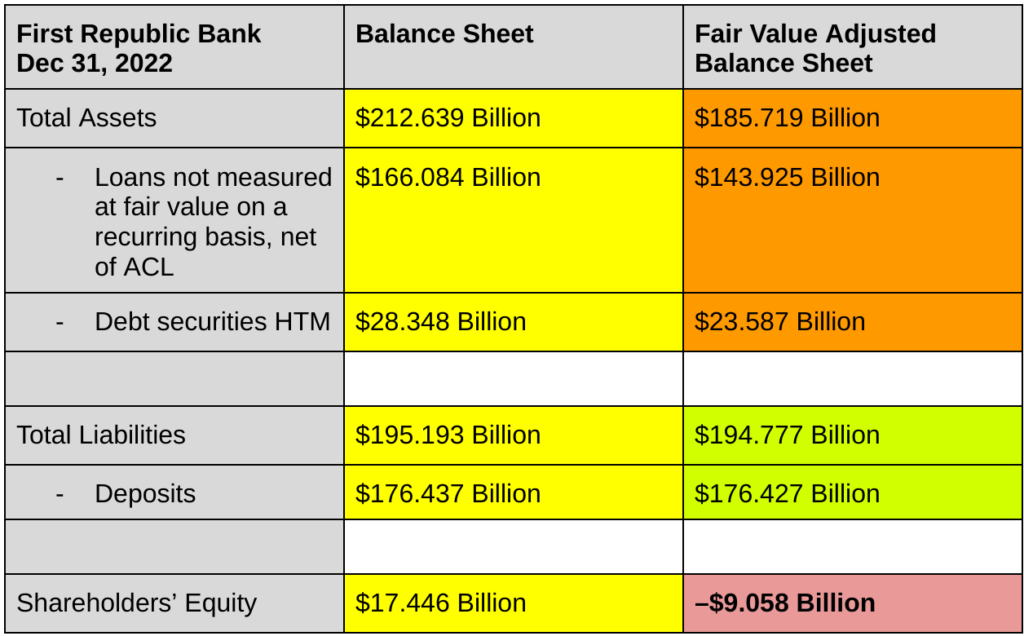

The problem is that the company is more than $9 billion underwater, despite the company’s balance sheet reporting more than $17 billion of shareholders’ equity. The difference between the financial truth (negative $9 billion of equity) and the official financial fiction (positive $17 billion of equity) is $26 billion of accounting lies. The result is that First Republic’s balance sheet overvalues certain assets by tens of billions of dollars but undervalues liabilities only slightly, as shown in the table below.

In this article, I’m going to explain:

- The 3 accounting rules (i.e. mathematical lies) that cause the biggest distortions to U.S. bank balance sheets (including the accounting rule that allowed First Republic to overstate its shareholders’ equity by more than $26 billion).

- How to un-distort a bank balance sheet to calculate true shareholders’ equity and find investment opportunities that most people miss.

Let’s dive in.

Lie #1: The majority of assets on a bank’s balance sheet are not reported at fair market value

Banks have two main types of assets on their balance sheet:

- Loans (e.g. mortgages, credit card debt, business loans, etc)

- Debt securities (e.g. Treasury bonds, mortgage-backed securities, and other bundles of loans that get reclassified as securities). For the accounting nerds, this includes debt securities classified as “held-to-maturity” and “available-for-sale” but not securities classified as “trading assets”.

Investments in debt securities and loans (together, the “debt portfolio”) typically constitute 50-95% of a bank’s assets. Larger banks tend to be on the low end of that range (50-75%) while smaller banks tend to be on the high end of that range (75-95%). These numbers are illustrated in the table below which shows the debt portfolio sizes for various publicly traded U.S. banks.

| Bank | Total Assets | Debt Portfolio (as % of total assets) |

| JP Morgan Chase | $3.67 Trillion | 48% |

| Bank of America | $3.05 Trillion | 62% |

| Wells Fargo | $1.88 Trillion | 72% |

| U.S. Bancorp | $675 Billion | 80% |

| PNC | $557 Billion | 83% |

| Truist | $555 Billion | 84% |

| BNY Mellon | $406 Billion | 51% |

| First Republic Bank | $213 Billion | 93% |

| Fifth Third Bancorp | $207 Billion | 82% |

| New York Community Bancorp | $90.1 Billion | 87% |

| Comerica | $85.4 Billion | 84% |

| East West Bank | $64.1 Billion | 88% |

| Wintrust | $52.9 Billion | 87% |

| Pacwest Bancorp | $41.2 Billion | 87% |

| SoFi | $19.0 Billion | 75% |

| Amalgamated Financial | $7.84 Billion | 95% |

| Meridian | $2.06 Billion | 93% |

| Citizens Community Bancorp | $1.82 Billion | 91% |

| Bank of South Carolina | $653 Million | 92% |

With such a large percentage of a bank’s assets tied up in loans and debt investments, small changes to the value of that debt portfolio can create large changes to (1) the bank’s shareholder equity, (2) the bank’s regulatory compliance with minimum capital requirements, and (3) the bank’s ability to fully repay depositors. That means it’s important to know how banks assign values to their debt portfolio assets, and how much those assigned values might differ from the market values of those same assets.

How U.S. banks value loans and debt securities

There are two main ways that a bank is legally allowed to value loans and debt securities on its balance sheet:

- Fair value (aka market value)

- Amortized cost (aka the outstanding principal, with minor adjustments)

The fair value of a loan or debt security is defined as the price that would be received to sell that asset on the open market under normal conditions. For debt securities such as Treasury bonds or mortgage-backed securities, there is often an actively traded market which allows banks to determine fair value by simply “marking-to-market”. For loans, there is often not any actively traded market since each bank writes loans with different contractual terms and for a different set of customers. For those loans, banks make estimated guesses of what the loans would sell for based on financial models.

On the other hand, the amortized cost of a loan or debt security has little to do with the asset’s market value. Instead, the amortized cost of a loan (or other debt asset) is just the current outstanding principal of the debt, with minor adjustments for fees on originated loans or premiums/discounts on purchased loans.

Notably, the amortized cost of a loan is usually almost exactly the same as the market value of that loan when the loan is originated. However, as interest rates change over time, the difference between the loan’s fair market value and its amortized cost can grow substantially.

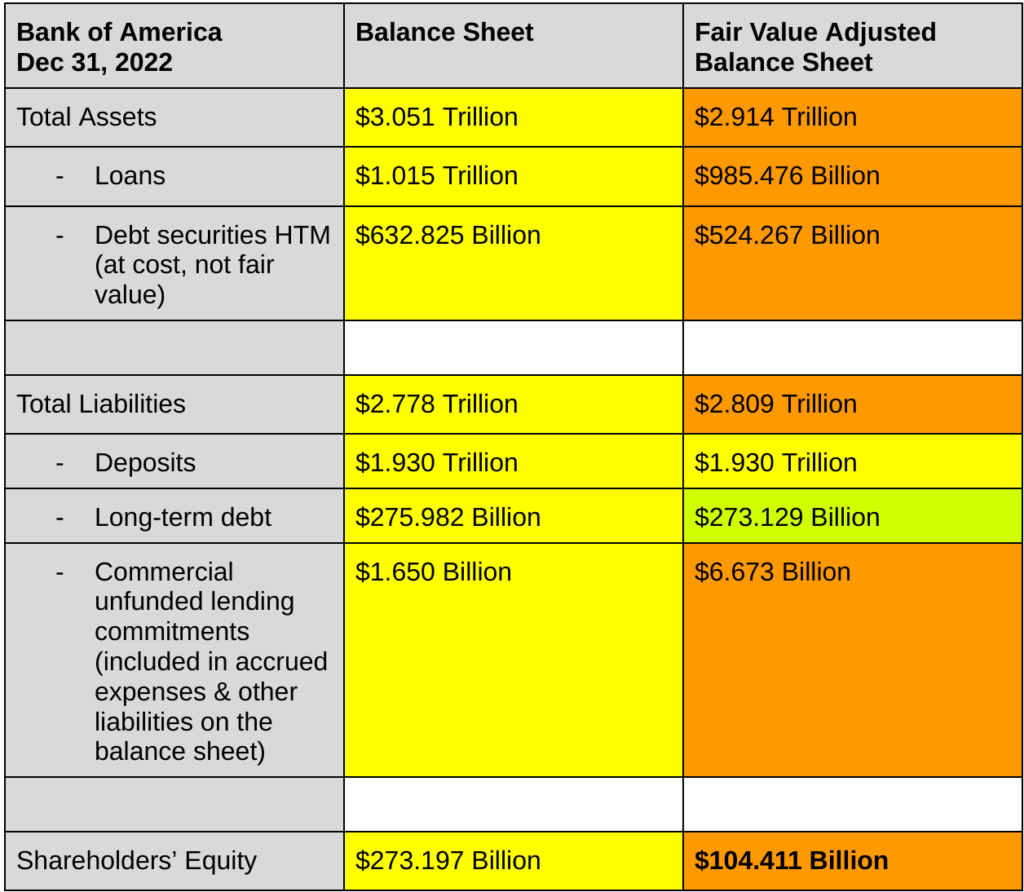

Example 1

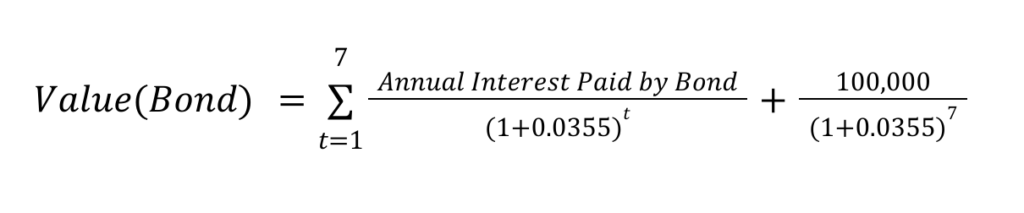

On March 20, 2020, Sad Bank buys a 10-year, $100,000 Treasury bond that pays out 0.92% interest annually. We’ll call that bond B20 (because it was bought in 2020). On March 20, 2023, Sad Bank buys a 7-year, $100,000 Treasury bond that pays out 3.55% interest annually. We’ll call that bond B23.

How much is each bond worth on March 20, 2023?

The amortized cost is easy. Treasury bonds are interest-only loans so the outstanding principal (amortized cost) of both B20 and B23 is still $100,000 as of March 20, 2023.

However, if you offered to give me either B20 or B23 for free on March 20, 2023, I would definitely choose B23. The reason is that both bonds will pay out $100k when they expire on March 20, 2030, and both bonds will make exactly the same number of interest payments on the same dates until then, but the total interest paid each year by B20 will only be $920 (0.92% of $100k) whereas the total interest paid each year by B23 will be $3,550 (3.55% of $100k).

That means the fair market value of B23 must be higher than the fair market value for B20 despite both bonds having the same amortized cost.

We know that the fair market value of B23 on March 20, 2023 is $100,000 since we bought it on that date for that price on the open market. So the fair market value of B20 must be less than $100,000.

Ordinarily, we wouldn’t be able to know exactly what the fair market value of B20 was without looking at real market data. However, since most banks assume Treasury bonds carry zero-risk, we can use a basic finance formula to estimate a 7-year bond’s value based on discounted cash flows when the prevailing interest rate is 3.55%:

Applying that formula to our bonds, we get:

For B23, we get a fair market value of $100,000 (just as expected). For B20, we get a fair market value of $83,948.70 (over 16% less than the amortized cost).

What percentage of bank balance sheet assets are reported using amortized cost vs fair value?

For most banks, 98-100% of their loan portfolio is reported on the balance sheet at amortized cost, not fair value. However, banks have more optionality when reporting debt securities.

Banks can categorize the debt securities they create or buy into two categories:

- Available-for-Sale (AFS)

- Held-to-Maturity (HTM)

Debt securities which are classified as AFS are reported on the balance sheet at fair value. However, the very same debt securities, if classified as HTM, can be reported by the bank at amortized cost instead. Some banks classify almost all of their securities as AFS. Other banks classify almost all their securities as HTM. Two identical banks can have VERY different values for total assets and shareholders’ equity just by choosing to classify the majority of their debt securities as HTM or AFS. Be wary of banks with most of their debt securities classified as HTM rather than AFS. They might be hiding big losses behind accounting trickery.

The table below shows the quantity of balance sheet assets which are recorded at amortized cost (including both loans and HTM debt securities) as a percentage of total balance sheet assets, for various publicly traded U.S. banks:

| Bank | Total assets | Assets recorded at amortized cost (as % of total assets) |

| JP Morgan Chase | $3.67 Trillion | 41% |

| Bank of America | $3.05 Trillion | 54% |

| Wells Fargo | $1.88 Trillion | 66% |

| U.S. Bancorp | $675 Billion | 67% |

| PNC | $557 Billion | 74% |

| Truist | $555 Billion | 68% |

| BNY Mellon | $406 Billion | 30% |

| First Republic Bank | $213 Billion | 91% |

| Fifth Third Bancorp | $207 Billion | 58% |

| New York Community Bancorp | $90.1 Billion | 76% |

| Comerica | $85.4 Billion | 63% |

| East West Bank | $64.1 Billion | 79% |

| Wintrust | $52.9 Billion | 80% |

| Pacwest Bancorp | $41.2 Billion | 74% |

| SoFi | $19.0 Billion | 3% |

| Amalgamated Financial | $7.84 Billion | 71% |

| Meridian | $2.06 Billion | 85% |

| Citizens Community Bancorp | $1.82 Billion | 82% |

| Bank of South Carolina | $653 Million | 50% |

| Median | $90.1 Billion | 68% |

The median bank in our sample had a balance sheet where 68% of assets were reported at amortized cost rather than fair market value. Let that sink in.

Banks are essentially huge margin traders that use customer deposit money to invest in loans and debt securities using 10-20x leverage. Like all margin traders, that makes the equity value of a bank highly sensitive to changes in asset values.

Example 2

Careless Bank has $92 billion of liabilities and $100 billion of assets, of which $68 billion are loans and debt securities reported at amortized cost. That means Careless Bank has:

Shareholders’ equity = $100 billion – $92 billion = $8 billion

However, if the fair value of Careless Bank’s portfolio of loans and debt securities is only $65 billion instead of $68 billion, then the actual shareholders’ equity is only:

Actual shareholders’ equity = $97 billion – $92 billion = $5 billion

That means overvaluing Careless Bank’s debt portfolio by only 4.6% ($68 billion instead of $65 billion) resulted in overestimating shareholders’ equity by a whopping 60% ($8 billion instead of $5 billion)!

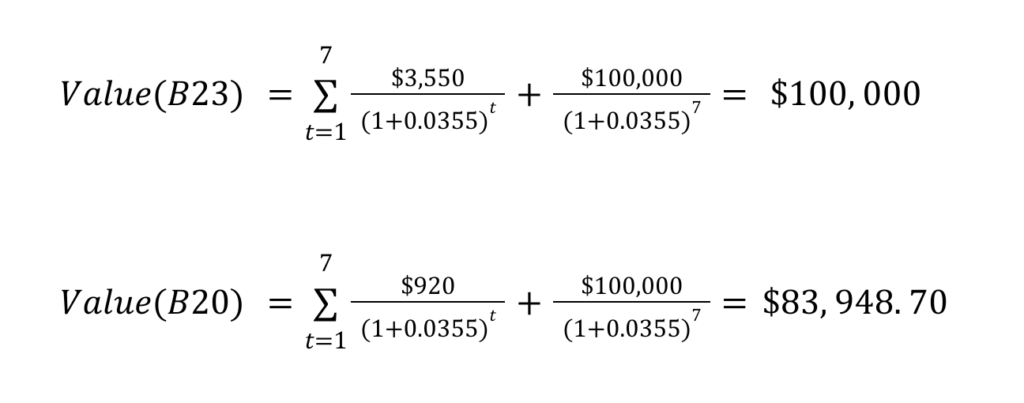

Example 3: Bank of America

Careless Bank was just a hypothetical bank used for example. Now let’s look at the second largest bank in the U.S. The table below shows a summarized version of Bank of America’s official balance sheet on December 31, 2022 as well as a modified version of that balance sheet after adjusting financial assets and liabilities to be reported at fair value.

Example 4: Truist

As you can see, fair value adjustments can MASSIVELY change the apparent solvency of a bank.

Lie #2: Disclosed “fair market values” can be manipulated

“In the latest Treasury auction, a 17-week Treasury bill with a par value of $100 sold for $98.54. Is the fair value of that bill $100 or $98.54?”

Bank balance sheet lie #1 was that banks report the majority of assets on their balance sheet NOT at fair value. However, banks must still disclose the fair value of those assets in the footnotes of their financial statements.

Bank balance sheet lie #2 is that those footnote disclosures of “fair value” still often differ from true “market value”. I’m going to explain why that is and how to account for it when analyzing a bank.

Why disclosed “fair values” are often wrong:

If you own a share of Tesla stock, you can just look at the last transaction on the NASDAQ stock exchange to determine its fair market value. Since half a million dollars of Tesla stock are traded during each minute of a trading day, the last stock trade is a very good indicator what you would be able to sell your own share of Tesla for if you wanted to.

Contrast that with your car. How much could you sell your car for if you had to sell it this week? According to Kelly Blue Book, my car is worth $16,777. According to Edmunds, it’s worth $21,994. Which is the true “fair value” of my car?

The problem is that my car is unique. There are other cars that are the same make and model as my car, but they have different manufacturer packages, different aftermarket upgrades, different numbers of miles on them, and different amounts of wear and tear. They also don’t sell everyday so even if there was a car identical to mine with the same packages, upgrades, miles, and wear and tear that sold 3 months ago, that wouldn’t necessarily be the same price that I could sell my identical car for today. This is the same problem that banks face, except instead of trying to find the fair value of cars, they are trying to find the fair value of loans.

As with cars, no two loans are exactly the same. They differ by the creditworthiness of the borrower, the debt-to-income of the borrower, the terms of the loan contract, the interest rate, the amount borrowed, the loan duration, and the type of collateral (if any) that the borrower has provided to secure the loan. Also as with cars, most loans are not actively traded which means even if there is a similar or identical loan that sold a few months ago, a bank doesn’t know for sure if that is the same price that the same loan would sell for today.

How do banks determine the fair value of loans & other illiquid assets?

Under U.S. generally accepted accounting rules (GAAP), bank loans and other financial assets fall into a three-level hierarchy based on how their fair values are determined:

- Level 1 assets. There are actively traded markets for level 1 assets which means fair values are determined by simply looking at the quoted prices from brokers, dealers, or exchanges. Examples of level 1 assets include cash, central bank reserves, and stocks listed on the NASDAQ or NYSE. The fair value of level 1 assets is assessed by simply looking at the market price which is readily available.

- Level 2 assets. These assets are not actively traded, but they are either similar to assets which are actively traded or their values are tied (directly or indirectly) to observable market variables. Examples of level 2 assets include consumer loans that are comparable to those packaged into actively traded mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The fair values of level 2 assets are estimated using matrix pricing, Black-Sholes options pricing, or other financial models which are based entirely on observable market variables (e.g. matrix pricing is based on the prices for a set of assets which are similar to the level 2 asset but which are actively traded).

- Level 3 assets. These assets are not substantially similar to any assets which are actively traded, nor are their values determined purely on the basis of observable market variables. Examples of level 3 assets include mortgage servicing rights (MSRs), complex derivative contracts, and certain specialized business loans. Fair values of level 3 assets are determined using financial models such as discounted future cash flows or proprietary models that depend significantly on at least one unobservable variable.

NOTE: Technically, GAAP’s fair value hierarchy is a hierarchy of methods for determining the fair value of assets, not of assets themselves. That means one bank may choose to treat a particular loan as a level 2 asset while another bank might treat the same loan as a level 3 asset because they value it using a different method.

The fair value hierarchy is important because it means that not all disclosures of fair market values are equally trustworthy. For example, if we look at Wells Fargo’s 2021 annual report, we see the following categorization of its primary financial assets:

| Financial Asset Category | Fair Value | % of Total |

| Financial assets (before derivative netting) | $1,848.626 Billion | 100% |

| – Level 1 assets | $354.591 Billion | 19.2% |

| – Level 2 assets | $645.774 Billion | 34.9% |

| – Level 3 assets | $848.261 Billion | 45.9% |

If we look at Fifth Third Bank’s 2021 annual report, we see an even higher percentage of financial assets in the level 3 bucket:

| Financial Asset Category | Fair Value | % of Total |

| Financial assets | $196.739 Billion | 100% |

| – Level 1 assets | $38.117 Billion | 19.4% |

| – Level 2 assets | $42.366 Billion | 21.5% |

| – Level 3 assets | $116.256 Billion | 59.1% |

For most banks, the majority of level 3 assets are loans, and these level 3 loans frequently account for 50% or more of all financial assets. That means even after we adjust a bank’s balance sheet to use fair values instead of amortized costs, roughly half of the balance sheet is valued using financial models that carry “significant uncertainty” and rely on rough estimates of unobservable variables.

Over a century of public market experience has taught us that when company executives have the freedom to make estimates with “significant uncertainty”, their estimates are statistically overoptimistic. That means in reality, we should expect these level 3 assets to be slightly overvalued on average.

There is also another reason to believe that “fair values” for level 3 loans are not necessarily fair. Level 3 loans are often valued using some version of a future cash flow model. However, a smart cash-flow-focused investor only buys investments that have a market price below the present value of future cash flows. Banks are (or should be) smart investors, and they are definitely cash-flow-focused investors. The most realistically possible buyers for a bank that wants to offload loans are other banks. That means if Bank A wants to sell some loans to Bank B, Bank B will probably only agree if the transaction (market) price is less than the present value of future cash flows of those loans. In other words, the future cash flow based valuation of the loans by the banks is almost certainly less than the actual market price of those loans.

How to fix a bank balance sheet filled with level 3 asset values:

To fix a bank balance sheet filled with level 3 loan assets so that it more accurately reflects the market value of assets, you’ll want to deduct a small percentage of the total dollar value of level 3 assets from the balance sheet.

If you think the bank’s executives have high integrity and you want to be optimistic, subtract 0.1% of the fair value of all level 3 assets. On the other hand, if the bank’s leadership seems like a scandal-magnet, and the culture rewards higher risk, you might want to subtract 2% or more of the fair value of all level 3 assets. Even Treasury bonds sometimes sell with more than a 1% discount from the par value, and yet some banks use Treasury bond interest rates (unadjusted for the discrepancy between par value and sale value) as the discount rates in future cash flow valuation models.

By the way, if you want to read more articles like this on a weekly-ish basis, subscribe to my free newsletter (of which this article is an example) where I talk about how to build better businesses and investment portfolios.

Lie #3: Off-balance sheet litigation liabilities

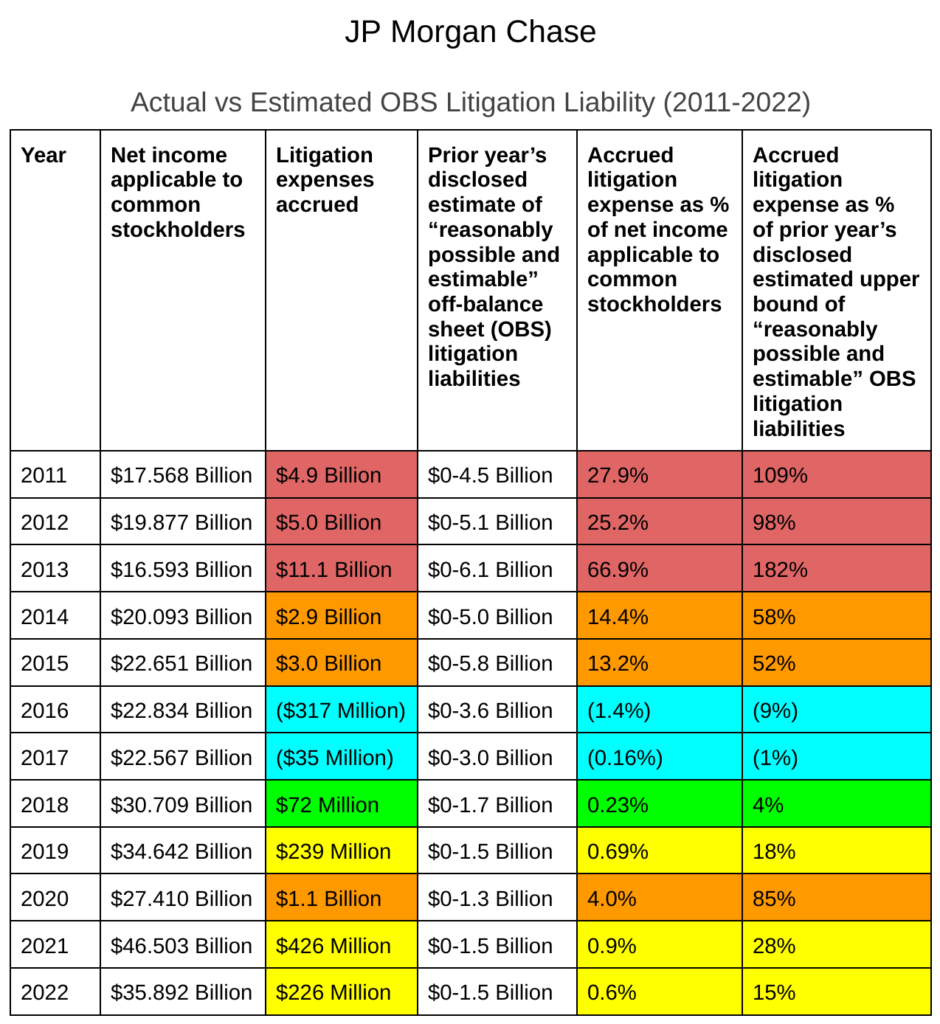

“In 2020, JP Morgan accrued $1.1 billion of litigation expense (equivalent to 4.0% of the bank’s net income applicable to common stockholders that year). None of that expense had been recorded on the balance sheet as a liability the prior year, despite the bank estimating in 2019 that they had up to $1.3 billion of reasonably possible future litigation costs.”

If a company borrows $1 million to acquire more customers, then it must record that $1 million as a liability on its balance sheet. However, if a company reduces its compliance standards in order to move more quickly and acquire more customers, incurring $1 million of legal liability in the process, the company does not have to record that $1 million liability on its balance sheet, despite the liability being just as real as the borrowed money.

The reason for this is that it’s difficult to know whether or not you actually have a litigation liability until a lawsuit is filed, and even then, you don’t know for sure whether you have a litigation liability or what the size of that liability will be until a verdict is reached in the case. And according to GAAP rules, companies don’t have to record contingent liabilities (i.e. liabilities that are dependent upon some future event occurring) on their balance sheet unless two conditions are satisfied:

- The contingency is “probable”

- The amount of the liability is “reasonably estimable”

Annoyingly, GAAP does not define when an event is “probable”. In fact, GAAP rules allow different companies to use different tests to determine whether or not an event is “probable”. That means one company can choose to define “probable” to mean an event with at least a 75% chance of occurring while another company can choose to define an event as “probable” if it has at least a 65% chance of occurring. And since companies are not required to disclose their criteria for determining when an event is “probable”, it’s impossible to do a precise calculation of expected value for contingent liabilities. However, Deloitte provides some general guidance on how to convert GAAP terminology to numerical probabilities:

- “Probable” = “Likely” = at least 70% chance of occurring

- “Reasonably possible” = 10-70% chance of occurring

- “Remote” = Less than 10% chance of occurring

GAAP says that remote contingent liabilities can be ignored completely, reasonably possible contingent liabilities must be disclosed in the notes of a financial statement but should not be included on the balance sheet, and probable contingent liabilities should be disclosed on the balance sheet. Actually, GAAP only provides those guidelines for contingent liabilities that are “reasonably estimable”. If a contingent liability is probable but can’t reasonably be estimated, it can still be kept off the balance sheet. Cue investor frustration.

If we assume bank executives report contingent liabilities without bias (big assumption), then the numbers provided by Deloitte imply we should expect the average reported contingent liability to have an 85% chance of occurring and the average disclosed-but-not-reported contingent liability to have a 40% chance of occurring.

That means even if we assume the entire amount of accrued (i.e. reported) litigation expense each year by a bank is for contingent liabilities rather than actual concrete liabilities, we should expect the the reported litigation liability to be (on average) understating the actual expected value of all contingencies that become realized litigation liabilities.

The table below shows the actual amount of litigation expense accrued by JP Morgan in each year from 2011-2022 compared with the bank’s prior year disclosure of off-balance sheet (OBS) “reasonably possible and estimable” contingent litigation liabilities.

The median ratio of this-year’s-accrued-litigation-liability to last-year’s-predicted-OBS-litigation-liability for JP Morgan from 2011-2022 was 56.5%.

In case you think that high cost of litigation is purely due to the Financial Crisis, let me inform you that over the three year period from 2004-2006, JPM accrued $5.752 billion of total litigation expense on $27.324 billion of net income applicable to common stockholders. That means during those years, the litigation expense was over 21% of total net income applicable to common stockholders.

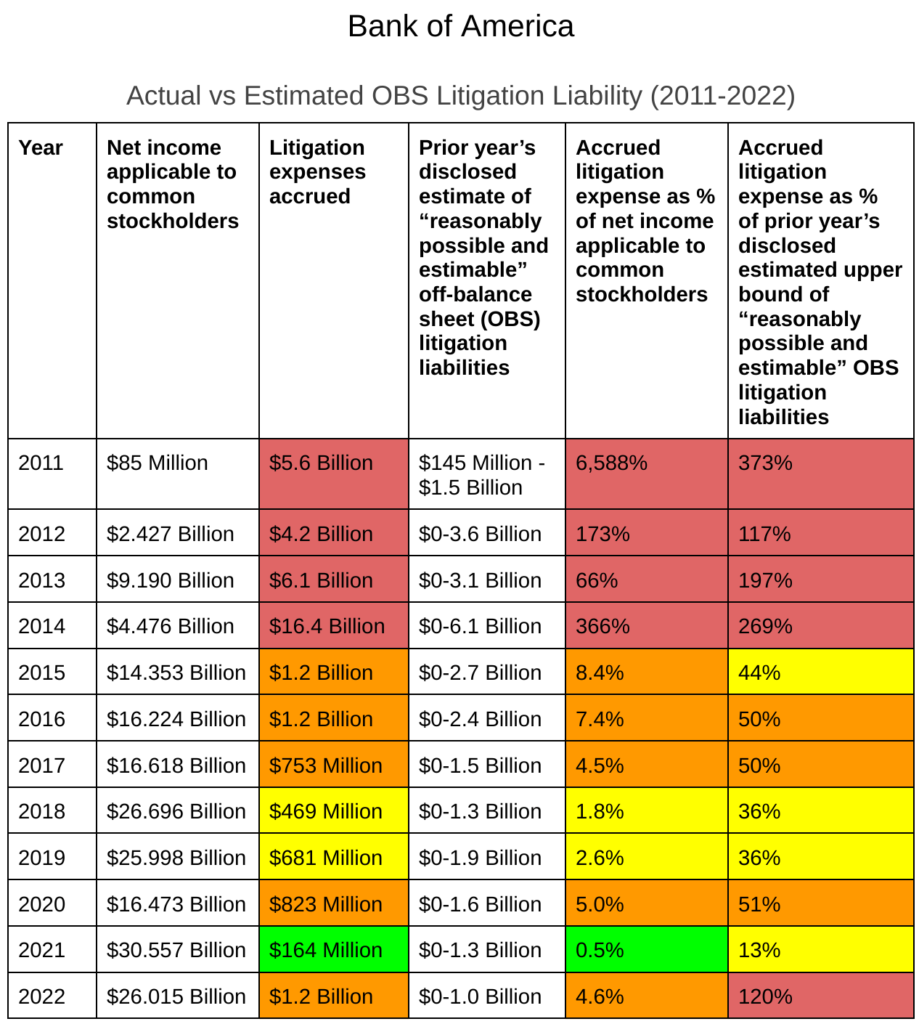

If we look at Bank of America, the litigation liabilities are also extreme:

The median ratio of this-year’s-accrued-litigation-liability to last-year’s-predicted-OBS-litigation-liability is 50%.

How to adjust a bank’s balance sheet to account for off-balance sheet litigation liabilities:

Add a liability to the bank’s balance sheet to account for the expected value of incurred but not accrued contingent litigation liabilities. The size of this new liability could optimistically be set at 10-50% of the amount of disclosed OBS “reasonably possible and estimable” contingent litigation liabilities. For many small banks, this amount will be zero. However, for larger banks and even smaller banks during recessions, this amount will often be nonzero.

How to “Correct” a Bank Balance Sheet Step-by-Step

Step 1: Identify the loans, HTM securities, and other financial assets on the balance sheet that are recorded at amortized cost rather than fair value. Locate the fair value disclosures of those assets in the financial statement notes. Replace the amortized cost values of those assets with the fair values of those assets on the balance sheet.

Step 2: Repeat step 1 but for liabilities instead of assets. The majority of liabilities held by banks are recorded at fair value already, so this will produce a much smaller adjustment than step 1.

Step 3: If you think the bank’s executives and work culture have high integrity and you want to be optimistic, subtract 0.1% of the fair value of all level 3 assets. On the other hand, if the bank’s leadership seems like a scandal-magnet and the culture rewards higher risk, you might want to subtract 2% or more of the fair value of all level 3 assets. Even Treasury bonds sometimes sell with more than a 1% discount from the par value, and yet some banks use Treasury bond interest rates (unadjusted for the discrepancy between par value and sale value) as the discount rates in future cash flow valuation models.

Technically, liabilities can also be assigned fair values through level 3 methods (although typically the amount of level 3 liabilities is far smaller than the amount of level 3 assets on a balance sheet). If you want to be conservative, only make the adjustment described above to the “net” quantity of level 3 assets obtained by first subtracting off the total quantity of level 3 liabilities. If you are more skeptical and believe as I do that bank managers are often (consciously or subconsciously) biased so that they slightly overvalue assets but not liabilities, then just don’t make any adjustments for level 3 liabilities.

Step 4: Add a liability to the bank’s balance sheet to account for the expected value of incurred but not accrued contingent litigation liabilities. The size of this new liability could optimistically be set at 10-50% of the amount of disclosed OBS “reasonably possible and estimable” contingent litigation liabilities. For many small banks, this amount will be zero. However, for larger banks and even smaller banks during recessions, this amount is often nonzero.

NOTE: You can take your step 4 analysis a bit farther by looking through the disclosures of the details of the OBS reasonably possible litigation liabilities and guessing what percentage of those liabilities would likely be covered by insurance if they were realized.

Appendix A: Other off-balance sheet liabilities

“Reasonably possible” litigation liabilities are not the only type of activities hiding off balance sheet. A more comprehensive list of types of fully or partially off-balance sheet activities that banks sometimes engage in include:

- Loan commitments

- Letters of credit (LOC)

- Travelers LOC

- LOC sold for cash

- Commercial LOC

- Standby LOC

- Revolving underwriting facilities

- minority interests in Variable Interest Entity (VIE)

- Due to lobbying efforts by banks, the FASB rules for VIEs were relaxed [post financial crisis], which enabled banks to continue pouring debt in off-balance-sheet entities.

- When a company owns a majority interest in a VIE, the holdings must be disclosed in the consolidated balance sheet of the company. The consolidation is not mandatory if the company is not the primary beneficiary of the VIE though.

- Pending lawsuits

- Liabilities from pending lawsuits are only recorded on the balance sheet when they are “reasonably estimable” and “more than likely to be incurred”, both of which are subjective qualifiers that are applied inconsistently across the banking industry.

- Indemnification agreements (contingent liabilities)

- Indemnifying executives of the company against certain types of lawsuits

- Indemnifying companies that partner with the bank (e.g. VISA) from certain types of lawsuits

- Indemnifying foreign investors in certain securities issued by a bank against changes in U.S. tax law that could negatively affect those investors

- Indemnifying an acquirer of a bank subsidiary against certain types of lawsuits or losses related to the prior operations of that subsidiary

- Membership in certain securities and derivatives exchanges and clearing houses both in the U.S. and abroad

- Membership in some of these organizations requires member banks to share in losses to that organization caused by (i) default of another member, and/or (ii) bad investments of margin funds contributed by members.

- The maximum liability for losses as a member of some of these organizations can exceed the amount of margin already contributed by that member.

- Example: In JP Morgan’s 2022 annual report, they disclosed an off-balance sheet maximum possible exposure (when estimable) for such membership loss responsibilities of over $191 billion.

- Financial guarantees

Many of these activities affect both assets and liabilities. For example, a loan commitment represents a promise to transfer money to someone else (which decreases liquidity and demands the same amount of money as if the bank had a debt payment of the same size), but it also represents an asset (the loan asset created once the loan commitment is fulfilled).

The exact impact of these activities on a bank’s balance sheet can be difficult to quantify, but the investor who is determined to extract alpha from bank stocks should at least make the attempt. In my opinion, the most interesting of these OBS activities are contingent liabilities such as pending lawsuits, indemnity agreements, and other guarantees. For example, as of the end of 2022, JP Morgan has a contingent liability which will be realized if certain changes are made to the U.S. tax code. Since cultural, political, and demographic trends suggest significant tax changes will be made over the next 10 years, JPM’s tax-contingent liability is an especially interesting type of contingent liability to analyze. You might be able to anticipate a future miss in the bank’s earnings before other investors realize what is happening.

A Quick Note on Variable Interest Entities (VIEs)

VIEs were a big problem during the financial crisis. However, rules around VIEs have gotten a lot stricter since then, and for the sample of banks I looked at when writing this article, I didn’t note any significant balance sheet distortions due to VIEs.

The maximum potential exposure to losses relative to investments in VIEs is generally limited to the sum of the outstanding book basis and unfunded commitments for future investments.

Appendix B: CECL

One of the most important balance sheet items for banks is the allowance for credit losses (ACL). This is essentially the amount of money the bank expects to lose from borrowers defaulting on loans.

Before 2020, banks used an incurred loss method where they only reported such losses as they were actually incurred. However, that system came with problems. In particular, it systematically overestimated the value of loan assets on a bank’s balance sheet, made the balance sheets of rapidly growing banks appear to be growing even faster than they actually were, did not always account for the differences in yearly loss rates for loans at different points in their life cycles, and did not anticipate increases to expected loan losses based on changing macroeconomic conditions.

Motivated by those shortfalls, regulators devised a replacement for the incurred loss reporting system: CECL.

CECL stands for “Current Expected Credit Losses”. Under CECL, banks must estimate the total losses over the life of a loan (the current expected value of credit losses over the life of a loan) and subtract that total value of those expected losses from the value of the loan asset on the balance sheet.

The new accounting rules do not dictate a particular methodology that banks must use to make CECL estimates, which means a variety of methods have been implemented by different banks. Some of these methods include:

- Vintage. Based on historical data. Similar to the incurred loss method.

- PD/LGD. Make separate estimates for the probability of a loan defaulting (PD) and the expected loss given default of a loan (LGD).

- WARM = Weighted-Average Remaining Maturity. This method uses an open pool concept instead of a closed pool concept.

- SCALE = Scaled CECL Allowance for Losses Estimated. This is a method for smaller banks.

Different banks adopted CECL between January 1, 2020 and January 1, 2023. As such, it’s too soon to say how much CECL deviates from real loan losses over time, but given the amount of subjective judgement that can go into CECL estimates, it’s quite possible that bank managers may abuse CECL to underestimate actual expected losses.

Appendix C: Level 3 assets example: Signature Bank

As of December 31, 2021, Signature Bank had $117 billion of financial assets as measured by fair value, and $65 billion (55%) of those were level 3 assets. Over $64 billion of that $65 billion consisted of loans.

Signature’s level 3 assets included pooled trust preferred securities, SBA loan interest-only strip securities (packaged by Signature Bank itself), certain private collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs), certain commercial loans, private equity investments, and complex OTC derivatives.

Level 3 assets were valued using internally developed valuation techniques and assumptions such as discount rates, credit spreads, default and delinquency rates, and prepayment speeds. Valuation techniques included cash flow and credit analyses.

Appendix D: Off-balance-sheet contingent liabilities are not specific to banks

While large banks often carry a variety of off-balance-sheet (OBS) contingent liabilities from activities including litigation, revolving credit lines, and loan commitments, many types of OBS contingent liabilities are not specific for banks. For example, almost any public company could have OBS contingent liabilities related to:

- Litigation (e.g. the healthcare industry has significantly more OBS litigation liability than the banking industry)

- VIEs (e.g. many companies in the energy sector have VIEs)

- Indemnification agreements

Glossary

ABCP = Asset-Backed Commercial Paper. An ABCP is a short-term money-market security that is issued by a special purpose vehicle (SPV).

ACL = Allowance for Credit Losses

ACLC = Allowance for Credit Losses on Off-Balance Sheet Credit Exposures

ACLLL = Allowance for Credit Losses on Loans and Leases

AFS = Available-for-sale

AFX = American Financial Exchange

AICPA = American Institute of Certified Public Accountants

ALLL = Allowance for Loan and Lease Losses

AMERIBOR = American Interbank Offered Rate (a proposed alternative to LIBOR)

AOCI = Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income

ARM = Adjustable Rate Mortgage

ARO = Asset Retirement Obligation

ARRC = Alternative Reference Rates Committee. The ARRC is a steering committee comprised of large U.S. financial institutions tasked with helping to devise a LIBOR replacement.

ASC = Accounting Standards Codification

ASU = Accounting Standards Update. An ASU is a notice of changes to U.S. GAAP standards issued by FASB.

BHC = Bank Holding Company

BHCA = Bank Holding Company Act of 1956

BOLI = Bank Owned Life Insurance

BSBY = Bloomberg Short-Term Bank Yield Index. This is a credit-sensitive borrowing rate that has been proposed as an alternative to LIBOR.

CAPM = Capital Asset Pricing Model

CDR = Constant Default Rate

CECL = Current Expected Credit Losses. CECL was described in FASB standard ASC 326 as a replacement method for ILM (the Incurred Loss Method) that SEC filers could use to determine an allowance for estimated loan and lease losses. Most SEC filers began using the standard between January 1, 2020 and January 1, 2023.

CECL was created as a replacement to ILM because ILM requires banks to wait until they actually incur losses before updating their loan loss allowances. In the wake of the financial crisis, regulators deemed that approach to be too reactionary so they came up with the CECL method as a replacement. Under CECL, a bank must use historical information, current market conditions, and expectations of the future economic environment when determining allowances for credit losses (ACLs). In other words, ILM is purely backward-looking whereas CECL is also foreward-looking. In theory, that means CECL should be more accurate. In practice, it may be more accurate, but it may also be much less accurate since forward-looking estimates are always easier for a company’s management to manipulate than historical data.

CET1 = Common Equity Tier 1

CFE = Collateralized Financing Entity

CMO = Collateralized Mortgage Obligation

CMT = Constant Maturity Treasury index rate (published by the Federal Reserve)

COFI = Cost of Funds Index. COFI is a federal benchmark interest rate published by Freddie Mac around the 20th of each month and used for some types or mortgage loans and securities. It is calculated by taking the sum of the monthly average interest rates for marketable Treasury bills and Treasury notes, dividing by two, and then rounding to three decimal places.

CRA = Community Reinvestment Act

CRE = Commercial Real Estate

DIF = The FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund

DTA = Deferred Tax Asset

DUS = Fannie Mae Delegated Underwriting and Servicing. A DUS MBS is a type of mortgage-backed security. Fannie Mae creates some DUS MBS where a security is backed by a single loan on a mutlifamily asset.

FCA = U.K. Financial Conduct Authority (a UK government body involved in regulating banks), OR False Claims Act (a piece of U.S. legislation)

FCRA = Fair Credit Reporting Act

FDIA = Federal Deposit Insurance Act

FFIEC = Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council. This is an important institution for bank investors to know about because FFIEC publishes “call reports” containing quarterly level bank data.

FHA = Federal Housing Administration

FHFA = Federal Housing Finance Agency (founded in 2008)

FHLB = Federal Home Loan Banks (A set of 11 regional, U.S. government-sponsored banks that are wholesale suppliers of lendable funds to financial institutions of all sizes)

FHLMC = Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (commonly known as Freddie Mac)

FICC = Fixed Income Clearing Corporation

FIRREA = Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act of 1989

FNMA = Federal National Mortgage Association (commonly known as Fannie Mae)

FRB = Federal Reserve Board

GNMA = Government National Mortgage Association (commonly known as Ginnie Mae)

GAAP = Generally Accepted Accounting Principles in the U.S.

GLBA = Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act

GSE = Government-Sponsored Enterprise. In the context of a U.S. bank’s annual report, a reference to GSEs is likely to be a reference to Fannie Mae (FNMA) and/or Freddie Mac (FHLMC).

GSIB = Globally Systemically Important Bank

G7 = Group of 7 Nations:

- United States

- United Kingdom

- Canada

- Japan

- Germany

- France

- Italy

HARP = Home Affordable Refinance Program

HELOC = Home Equity Line of Credit

HFI = Held for Investment. HFI loans are loans held for long-term investment purposes and are not expected to be sold.

HFS = Held for Sale. HFS loans are accounted for in a similar way to AFS debt securities at a bank.

HQLA = High-Quality Liquid Assets. These consist of cash and certain other high-quality liquid securities as defined in the LCR rule.

HTM = Held-to-maturity

ILM = Incurred Loss Method (the predecessor to CECL that banks used to determine ALLL — an allowance for loan and lease losses)

IRLC = Interest Rate Lock Commitments

ISDA = International Swaps and Derivatives Association

LCR = Liquidity Coverage Ratio

LDA = Loss Distribution Approach

LGD = Loss Given Default

LIBOR = London Interbank Offered Rate

LIHTC = Low-income housing tax credit

LOC = Letter of credit. An LOC is a document issued by a bank on behalf of one of its customers, authorizing a third party to draw drafts on the bank up to a stipulated amount under specific terms and conditions.

LOCOM (or sometimes LCM) = Lower of Cost or Market. LOCOM is a conservative approach to valuing a financial asset by valuing it at the lower of (1) amortized cost, or (2) fair market value.

LTV = Loan-to-Value

MBS = Mortgage-Backed Security

MLTN = More Likely Than Not

MNA = Master Netting Agreement

MSA = Mortgage Servicing Asset (or Metropolitan Statistical Area)

MSR = Mortgage Servicing Right

MSRB = Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board

OAS = Option Adjusted Spread(s)

OCC = Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. The OCC is an independent bureau within the U.S. Treasury Department that was established by the National Currency Act of 1863. The purpose of the OCC is to charter, regulate, and supervise all national banks, consumer-facing credit unions and other thrift institutions, and federally licensed branches and agencies of foreign banks in the U.S.

OCI = Other Comprehensive Income

OFAC = U.S. Treasury Department Office of Foreign Assets Control

OREO = Other Real Estate Owned. OREO is a bank balance sheet asset consists of real estate that the bank owns but does not use in its business (e.g. properties that were foreclosed on but haven’t been sold at auction).

PCAOB = Public Company Accounting Oversight Board

PCI = Purchase Credit Impaired. PCI is an outdated GAAP category for debt assets that has since been replaced by the more flexible PCD category.

PCD = Purchase Credit Deteriorated. A loan asset is PCD if it is “purchased with more than insignificant credit quality deterioration” since origination. The concept is discussed in detail here.

PD = Probability of Default

RESPA = Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act

RMBS = Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities

ROU = Right-of-Use (Asset). The primary example of an ROU asset is a building you lease.

RUFC = Reserve for Unfunded Lending/Loan Commitments

SCALE = Scaled CECL Allowance for Losses Estimated. SCALE is one of the possible CECL methodologies for calculating a regulatorily acceptable CECL allowance for credit losses (ACL)

SFAS = Statement of Financial Accounting Standards

SOFR = Secured Overnight Financing Rate. SOFR is the average cost (i.e. interest rate) for banks to borrow cash overnight with Treasury securities as collateral. SOFR was selected by the ARRC as its recommended alternative to LIBOR. However, unlike LIBOR, SOFR is a rate that does not take bank credit risk or term into account. As such, it will likely be less correlated with actual funding costs for financial institutions. Other possible alternatives to LIBOR include the Bloomberg Short-Term Yield Index (BSBY), which is a credit sensitive rate.

SPE = Special-Purpose Entity

TDR = Troubled Debt Restructuring

TRS = Total Return Swap

TILA = Truth-in-Lending Act

VIE = Variable Interest Entity. A VIE is a business entity that lacks equity investors or whose equity investors do not have a controlling financial interest in the entity through their equity investments. Instead, a VIE is designed for a person (deemed the “primary beneficiary”) to be able to control it even if that person does not own a majority of the voting rights. Usually this is accomplished through some sort of contractual relationship. A VIE may be any type of business entity (e.g. a limited partnership, corporation, or trust).

WARM = Weighted Average Remaining Maturity. This is a CECL methodology to calculate an allowance for credit losses (ACL). It uses an “open pool/cohort” concept rather than a “closed pool/cohort” concept like some other CECL methodologies.

Q factors (qualitative factors) under CECL are qualitatively estimated variables that go into qualitative adjustments to CECL ACL calculations. Some examples of Q factors that banks may use are (1) the nature of the bank’s financial assets, (2) the quality of the bank’s credit review system, (3) the experience and ability of lending and collections management staff at the bank, (4) expected changes to the general market in a geographic area due to specifics of the local economy, and (5) the possible effect of long-tail “black swan” risks such as natural disasters or material data breaches.

Under U.S. GAAP, a contingency is an existing condition, situation, or set of circumstances involving uncertainty as to possible gain (gain contingency) or loss (loss contingency) to an entity that will ultimately be resolved when one or more future events occur or fail to occur.

Fair value of an asset or liability is defined by GAAP rules as the price that would be received to sell that asset or paid to transfer that liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.

The primary beneficiary of a VIE is the party that has both:

- The power to direct the activities of the VIE that most significantly impact the entity’s economic performance, AND

- The obligation to absorb losses or the right to receive benefits that could be significant to the VIE.

The primary beneficiary of a VIE is required to consolidate the VIE into their financial statements. An example of a VIE is an investment fund set up as a limited partnership. In that example, the general partner would be the primary beneficiary.

References

[1] FDIC regulations – safety manual section 3.8 — Off-balance sheet activities

[2] NY Fed – What happens when regulatory capital is marked to market? (2018)

[3] Minkwan Ahn. The Market’s View on Accounting Classifications for Asset Securitizations. PhD Dissertation. The Ohio State University. 2014.

[4] SFAS 166 — New FASB standard in 2009 that eliminated the QSPE exemption from applying VIE accounting

[5] SFAS 167 — New FASB standard in 2009 that replaced the quantitative analysis for consolidation required under FIN 46(R) [relating to QSPE or VIE accounting] with a qualitative analysis

[6] ASC Topic 450 — Contingencies

[7] ASC Topic 820 — Fair Value Measurement

[8] PWC — Inputs to fair value measurement and hierarchy (2022)

[9] FASB memo on transferring loans and debt securities between HFS/AFS and HFI/HTM categories

[10] Interpreting “likely”, “possible”, and similar phrases by IFRS auditors & practitioners

[11] Litigation Cost Survey of Major Companies in the U.S.

[12] Deloitte Roadmap: Contingencies, Loss Recoveries, and Guarantees. See Section 2.3.1 for numerical probability interpretations of the terms “probable”, “likely”, “remote”, and “reasonably possible” when describing contingent liabilities.

[13] Jared Stauffer. CECL for Financial Institutions: An Analysis of the SCALE Method. PhD Dissertation in Economics, University of Nebraska (2022).

The Axiom Alpha Letter

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to my free weekly(ish) newsletter: The Axiom Alpha Letter (of which this article is an example). I talk about how to build better businesses and portfolios from first principles & data (rather than “best practices” which are often riddled with suboptimal and outdated assumptions).