An easement is a right to use or control someone else’s real property in a limited way.

For example, a utility company can have an easement that allows them to run a gas line that belongs to them through your property, and allows them to send workers onto your property to maintain and repair that gas line as necessary.

As another example, a farmer who lives on a piece of land with no public road access might have an access easement that allows him to drive over his neighbor’s private road in order to get to a public road nearby.

There are also many other types of easements such as drainage easements, conservation easements, and pipeline easements. In this article, I’m going to explain:

- What the different types of easements are,

- Whether or not you can block an easement,

- Which easements run with the land and which do not,

- The different ways easements can be created,

- How to determine how much an easement is worth,

- Who is responsible for maintaining easements,

- What the difference is between a right of way and an easement, and

- What the difference is between a negative easement and a restrictive covenant.

Along the way, I’ll provide lots of examples. Let’s jump in!

Types of Easements

Easements can be categorized along two dimensions:

- The easement is either positive (called “affirmative”) or negative, and

- The easement is either appurtenant or in gross

Affirmative vs negative easements

An affirmative easement is a right to use someone else’s property for a specific purpose such as walking over the land to get from A to B, driving over the land to get from A to B, or operating an underground power line that runs through the land.

A negative easement is a right that allows you to prohibit someone from performing specific actions on their own land. If that sounds weird and perhaps unfair, you aren’t alone in thinking so, which is why negative easements are less common than positive easements and why American courts limit the scope of activities that can be restricted by a negative easement. One example of a negative easement is a view easement that prohibits a neighbor from building any structures that would obstruct the view from a window on your property. Another example of a negative easement is a conservation easement that prohibits the development of land from its natural state.

NOTE 1: Not every prohibition on what a landowner can do on their own land comes from a negative easement. Some prohibitions instead come from “restrictive covenants” which are rooted in contract law rather than negative easements which are rooted in property law. In general, negative easements deal with “basic” things like prohibiting landowners from blocking views or sunlight. Restrictive covenants, on the other hand, are more general (since they are part of contracts) and can restrict almost any type of activity. More on this later.

Easements appurtenant vs easements in gross

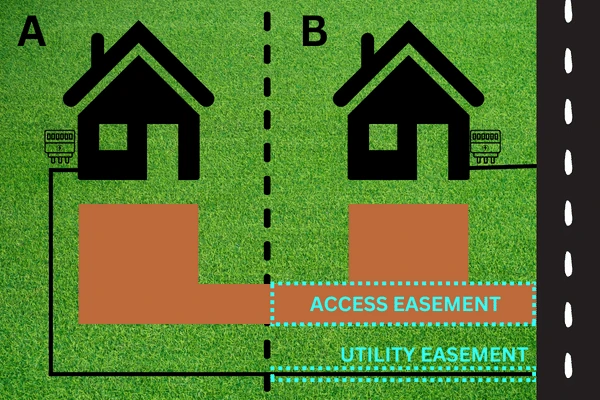

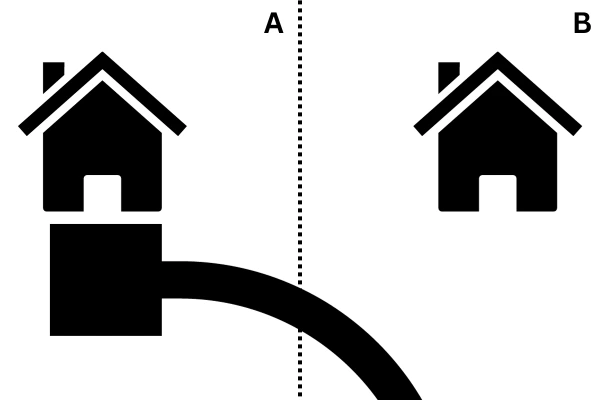

An easement appurtenant is a type of easement that links two parcels of land, where the owner of one piece of land has the right to use an adjoining piece of land that belongs to someone else. The situation is illustrated in the diagram below with land parcels A and B. In this diagram, the owner of parcel A has two easements in parcel B: a utility easement and a vehicular access easement. Because the owner of parcel A has the right to use parcel B, we call parcel A the “dominant tenement” or “dominant estate” while we refer to parcel B as the “servient tenement” or “servient estate”.

The owner of the dominant tenement is the person who holds the easement, and the owner of the servient tenement is the person who is bound by the easement.

An easement appurtenant “runs with the land” which means if parcel A and/or parcel B change(s) ownership, the new owner(s) will still be connected by the same easements. Whenever there is ambiguity about the type of an easement, American courts will tend to construe an easement to be an easement appurtenant as opposed to the next type of easement we’ll discuss — an easement in gross.

Easements in gross

An easement in gross is a type of easement which only involves a single piece of land. The easement is held by a third party (individual or organization). The most common example of an easement in gross is a utility easement where the utility company is the third party who owns the easement.

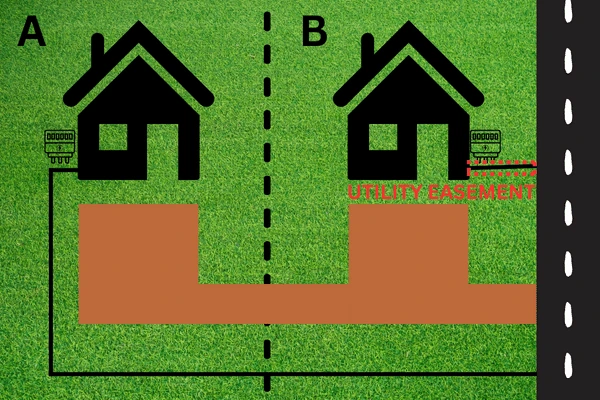

NOTE 2: You may be wondering why I previously referred to the utility easement highlighted in blue in the diagram above as an easement appurtenant when I just said utility easements are easements in gross. It’s because the utility easement highlighted in blue is an easement for the utilities of an adjoining landowner. In contrast, the utility line running directly to the house on parcel B is a more typical example of a utility easement. This easement (shown in red below) is an easement in gross.

Besides utility easements, other examples of easements in gross are pipeline easements.

The 4 types of easements

We now know that easements can be positive (affirmative) or negative, and appurtenant or in gross. That means all together, there are 4 types of easements:

- Affirmative appurtenant easements

- Negative appurtenant easements

- Affirmative easements in gross

- Negative easements in gross

The table below shows examples of each of type of easement.

| Affirmative – Entitles the easement holder to use the property owned by another for a limited purpose | Negative – Entitles the easement holder to compel the possessor of a property to refrain from taking part in certain activities | |

| Easement Appurtenant – An easement giving a limited interest in or right to use one property, to the owner of a different property. It runs with the land. | 1) Joe sells Bob a landlocked parcel of land with no public road access except via a private road that cuts across other property owned by Joe. The sale conveys an implied easement appurtenant to Bob, allowing him to use Joe’s road to access his (Bob’s) land. 2) A neighbor’s right to use a trail along your property as a shortcut to the beach. This is a type of access easement. | 5) A view easement as in [Peterson v. Friedman 1958] which prohibits certain structures over a certain height for the benefit of the view from a neighboring property. |

| Easement in Gross – An interest in or right to use the land of another that is personal and typically ends at the easement holder’s death or when the property is transferred to a new owner. | 3) Right given by a landowner to another person to fish in the landowner’s pond. This type of easement is called a profit. 4) A utility easement giving a utility company the right to come onto land to operate, maintain, and repair utility equipment (e.g. power lines, poles, water lines, etc) | 6) A conservation easement |

Easements in gross that are of a personal or recreational nature cannot be transferred by the easement holder. However, commercial easements in gross (such as utility easements) often CAN be transferred by one easement holder to a new easement holder.

The 6 ways easements can be created

Easements can be created using 6 methods:

- Express grant

- Express reservation

- Necessity

- Implication

- Prescription

- Estoppel*

*NOTE 3: Easements by estoppel are not actually true easements. Instead, they are “irrevocable licenses”. However, they are treated essentially the same as easements, and many American courts refer to them as easements. This is also the position taken by the Restatement (Third) of Property which states that “[an] irrevocable license is treated the same as any other easement” unless the parties intended or reasonably expected that it would remain irrevocable only so long as reasonably necessary to recover expenditures.

Now let’s jump into how each method works.

1. Easements created by express grant

An easement created by express grant is just an easement that one person conveys to another explicitly. The statute of frauds requires this to be in writing if the easement will last for more than one year. Easements created by express grant are limited to the terms and purposes laid out in the express grant.

2. Easements created by express reservation

An express reservation is just like an express grant, but instead of a property owner conveying an easement to a second person, the property owner conveys the entire property to a second owner and retains an easement for himself. In legal words, the grantor conveys title to the land to another person but retains an easement to use the land for a special purpose.

Example: Bob sells his farm to Joe, but in the land sale contract, he includes a clause stipulating that he will still be able to use 100 square feet in the northeast corner of the farm to produce food for his own personal consumption. Bob has created an easement by express reservation.

NOTE 4: A reservation easement can ONLY be created for the use of the grantor themself. That means in our example above, Bob would not be able to reserve an easement for his friend Ron to use a small piece of the farm for personal vegetable growing after the sale. If Bob really wanted to achieve this however, he could do so indirectly by first transferring the property to Ron and then having Ron transfer the property to the new owner, retaining an easement for himself. In states that put a fee on property transfers though, this indirect method might be more cost than its worth.

3. Easements created by necessity

The first thing you should know is that negative easements cannot be created by necessity. Additionally, easements in gross cannot be created by necessity.

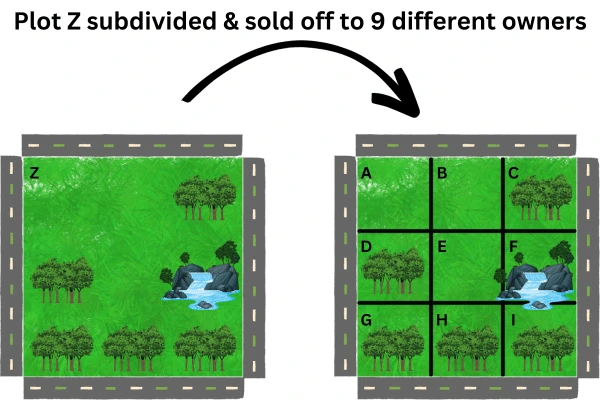

An easement by necessity is a type of affirmative appurtenant easement that can only exist between adjoining land parcels when both land parcels used to be owned by the same person and were subsequently split, with one of the child parcels being landlocked (i.e. having no direct public road access). This process is illustrated in the visual below.

Under common law, an easement by necessity is created with dominant estate E over servient estate B if two conditions are met:

- Unity of ownership prior to separation. At some point in the past, both parcels B and E must have been owned by a single owner. In our visual example above, this is true (the common owner is whoever owned the original plot Z).

- Strict necessity for the easement existed at the time of severance.

To prove strict necessity, the owner of the landlocked property (parcel E) must prove that the severance of title (i.e. the subdivision of plot Z into nine new plots) caused the property to be *absolutely* landlocked (i.e. entirely surrounded by adjoining landowners, giving the landlocked property owner no legal way of reaching their land). This strict necessity requirement is satisfied in our visual example above.

WARNING: Common law easements by necessity are exceptions to the statute of frauds because they are interests in land that are implicitly conveyed by circumstances rather than any written agreement. That can make them unsuspecting traps for land buyers who may purchase property without realizing that a neighboring property has an easement by necessity over the buyer’s new land. This is especially important because title insurance may not cover unknown easements by necessity.

NOTE 5: Some states such as Florida have codified a second type of easement by necessity available via statute. Such easements are generally available in the same situations as implied easements by necessity but are created by a court and hence leave a record that can be checked in a thorough title search.

4. Easements created by implication

As with necessity, implication cannot create negative easements. Only affirmative appurtenant easements can be created by implication.

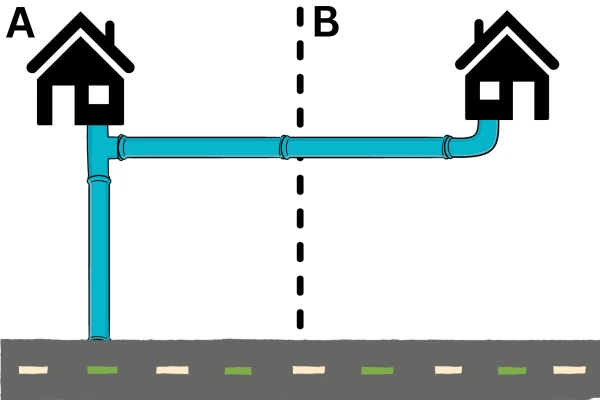

Example: Bob owns two plots of land, A and B. Bob builds a house on each property, but instead of running two separate sewer lines to connect the houses to the main public sewer line, he just runs one line from A to the main sewer line and then runs a connecting line from A over to B. This whole setup is visualized below.

After Bob finishes building the homes, he sells property A to Alice but forgets to mention anything about the sewer lines, but there is a marker on the parcel boundary which states that a shared sewer line is underground at that point. Bob, living on property B, gets an implied easement to continue using the sewer line on property A after the sale of property A.

The requirements for an easement to be created by implication are similar to but distinct from the requirements for an easement to be created by necessity. The requirements for implication are:

- Unity of ownership in the past. At some point in the past, both parcels A and B must have been owned by a single owner. This is true in our example above (Bob was the common owner).

- When unity of ownership was broken, lot B had apparent and continuous prior use of some part of lot A.

- The original owner expected the use to continue.

- Continued use is reasonably necessary (meaning any alternatives would be substantially more expensive). This requires more than mere convenience but less than strict necessity.

When is prior use “apparent”?

Many courts consider the term “apparent” to mean either visible or something that might be discovered by reasonable inspection (typically because of some observable artificial structure that might be examined or inquired about).

When is prior use “continuous”?

Different jurisdictions have interpreted this requirement differently. Some have interpreted “continuous” as involving a permanent fixture or fixture adapted to continuous use. Other jurisdictions have interpreted “continuous” as meaning capable of being enjoyed without any act of man. Those latter courts have often interpreted infrequently used private roads as not being used “continuously” while drains that may only be infrequently used are still deemed to be used “continuously”.

What’s the difference between an implied easement and an easement by necessity?

The biggest differences between the requirements for an easement by necessity and an easement by implication are (1) an easement by necessity requires strict necessity whereas an easement by implication only requires reasonable necessity and (2) an easement by implication requires intention of the original owner whereas an easement by necessity does not.

NOTE 6: Some jurisdictions use the term “easement implied by prior use” or just “easement by prior use” to mean what I have described here as an “easement by implication”. These jurisdictions also use the term “easement by implication” to mean, more generally, any easement which isn’t created by express agreement. By that definition, a common law easement by necessity and a common law easement implied by prior use would just be two subtypes of easement by implication.

Additionally, some jurisdictions do not recognize any easements implied by prior use unless such easements are easements by strict necessity. For example, prior to 1986, Florida courts generally allowed implied easements to be established on the basis described here, including the reasonable necessity requirement. However, a 1986 Florida Supreme Court case (Tortoise Island Communities v. Moorings Association) squashed that precedent and clarified that implied easements can only be created in Florida under conditions of strict necessity.

In Texas, the terms “prior use easement” and “easement by necessity” are used for two separate but closely related easement types, with the former requiring reasonable necessity and the latter requiring strict necessity. The main difference in Texas is that an easement by necessity is just a roadway access easement but can’t be e.g. a utility easement. In contrast, a prior use easement in Texas can be a utility easement or other non-access easement. Here is an excerpt from the 2014 Texas Supreme Court case (Hamrick v. Ward) which clarifies this:

“This case presents the Court with an opportunity to provide clarity in an area of property law that has lacked clarity for some time: implied easements. For over 125 years, we have distinguished between implied easements by way of necessity (which we refer to here as “necessity easements”) and implied easements by prior use (which we refer to here as “prior use easements”). We created and have utilized the necessity easement for cases involving roadway access to previously unified, landlocked parcels. Roadways are by nature typically substantial encumbrances on property, and we accordingly require strict, continuity necessity to maintain necessity easements. By contrast, we created and have primarily utilized the prior use easement doctrine for lesser improvements to the landlocked parcel, such as utility lines that traverse the adjoining tract. We have required, to some degree, a lesser burden of proof for prior use easements (reasonable necessity at severance rather than strict and continued necessity) because they generally impose a lesser encumbrance on the adjoining tract (e.g. a power line compared to a roadway). Today, we clarify that the necessity easement is the legal doctrine applicable to claims of landowners asserting implied easements for roadway access to their landlocked, previously unified parcels.”

Opinion of the Texas Supreme Court, 2014

That is different than in Florida where an easement by necessity can mean an access easement, a utility easement, or another type of easement.

Implied dedications & easements implied by a subdivision plat map

It’s worth noting that subdivision plat maps depicting (possibly ambiguously labeled or described) roads, parks, sidewalks, and utilities can also give rise to easements. Sometimes these easements are granted to the public or to a local government (in which case they are called dedications) while other times the plat map grants implied easements to owners of subdivision lots.

5. Easements by prescription

An easement by prescription is an easement obtained from a landowner without that landowner’s permission. Most American courts treat easements by prescription as analogous to adverse possession, but rather than a squatter taking ownership of your land, the typical example would be a neighbor obtaining an access easement by simply driving over your land without your permission for 20 years.

More generally, someone obtains a prescriptive easement by continuously and obviously trespassing onto your land to use it in some particular way over a long period of time. Exactly how long depends on which state you are in. For example, in many states such as Florida the land must be trespassed upon for 20 years before the trespasser obtains a prescriptive easement. In Texas, only 10 years are required. In California, only 5 years are required.

NOTE 7: It is not necessary for a single person to trespass onto land for the entire statutory period for a prescriptive easement to be created. If two or more people sequentially trespass onto the same land for the same reason, then their periods of usage are “tacked” together when determining whether the minimum time period has been met. For example, if Bob’s neighbor Joe parks on Bob’s land in California for 3 years without Bob’s permission, and then Joe sells his house to Sam who goes on to also park on Bob’s land without permission for another 3 years, then the combined 6 year parking period is greater than California’s required 5 year minimum period for prescriptive easements so a prescriptive easement will be deemed to exist, even though no single person parked on Bob’s land for 5 years or more.

Under common law, there are 5 requirements for a person to obtain a prescriptive easement in a piece of property they don’t own:

- The person must make actual use of the property for a particular purpose.

- The use must be “hostile“. That just means that the user does not have the property owner’s permission so that the owner has a legal claim that they could have used at any point to take the trespasser to court.

- The use must be “open and notorious“. That means the trespasser did not hide his or her usage of the property, and people could easily observe the trespasser using the property.

- The use was “continuous“. What exactly constitutes “continuous” depends on the situation. For example, the mere installation of a drain may mean that the drain is in “continuous” use, even if it only rains during 6 months of the year. In contrast, if someone only trespasses onto a private road for 6 months out of the year because they live in a different state for the other 6 months, then that road usage would NOT be continuous.

- The use must extend over a sufficiently long period of time, which is usually the same length of time as the statutory adverse possession period in that jurisdiction (which typically ranges from 5-20 years).

Because prescriptive easements arise by use, all prescriptive easements are affirmative easements. Negative easements cannot be created by prescription.

6. Easements by estoppel

Technically, easements are not created by estoppel. However, licenses (which are normally revocable at any time) can sometimes become irrevocable by estoppel, and some courts treat irrevocable licenses as equivalent to easements, and those courts will also sometimes refer to irrevocable licenses as easements by estoppel. Here’s how it all works.

A license is just a revocable permission for one person to let another person come onto their property. For example, event tickets grant the ticket holders license to be in the event venue. For another example, I give my friend a license to be on my property when I invite him over for dinner. For a third example, you may have an implied license to go onto someone’s porch and ring the doorbell if you do so at a reasonable hour and there are no “no trespassing” or “no soliciting” signs.

Those are all examples of ordinary licenses which are revocable at any time. So when does a license become irrevocable by estoppel?

The short answer is that a license can become irrevocable when the licensor gives license to a licensee and then the licensee relies on that license by investing resources. There are usually 3 requirements for this situation to occur:

- A landowner gives permission (license) to another person to use the land,

- The licensee relies, in good faith, on the permission given, by investing resources into the use (e.g. by constructing improvements related to their land use), and

- The landowner knew (or reasonably should have known) of such reliance.

However, some courts (see Henry v. Dalton, Supreme Court of Rhode Island 1959) reject the idea that reliance on oral permission can give rise to an easement by estoppel. These courts argue that such treatment would violate the statute of frauds by creating interests in land for more than 1 year without written agreement.

Key Cases:

- Kienzle v. Myers (Ohio Court of Appeals 2006)

- Holbrook v. Taylor (Supreme Court of Kentucky 1976)

- Henry v. Dalton (Supreme Court of Rhode Island 1959)

Summary: Which Types of Easements Can be Created by Which Methods?

| Affirmative – Entitles the easement holder to use the property owned by another for a limited purpose | Negative – Entitles the easement holder to compel the possessor of a property to refrain from taking part in certain activities | |

| Easement Appurtenant – An easement giving a limited interest in or right to use one property, to the owner of a different property. It runs with the land. | By Express Grant: YES By Express Reservation: YES By Necessity: YES By Prior Use (Implied): YES By Prescription: YES By Estoppel: YES | By Express Grant: YES By Express Reservation: YES By Necessity: NO By Prior Use (Implied): NO By Prescription: NO By Estoppel: NO |

| Easement in Gross – An interest in or right to use the land of another that is personal and typically ends at the easement holder’s death or when the property is transferred to a new owner. | By Express Grant: YES By Express Reservation: YES By Necessity: NO By Prior Use (Implied): NO By Prescription: YES By Estoppel: YES | By Express Grant: YES By Express Reservation: YES By Necessity: NO By Prior Use (Implied): NO By Prescription: NO By Estoppel: NO |

Examples of easements

| Type of Easement | Example | |

| 1 | Affirmative appurtenant easement by express grant | Joe has a beachfront property and sells an easement to his backyard neighbor, allowing the neighbor to walk over Joe’s property to get to the beach. |

| 2 | Affirmative appurtenant easement by express reservation | Zach, a developer, owns a large piece of land. He subdivides the land into 4 parcels. Three of the parcels (A,B,C) are small, side by side parcels which all share a boundary with the fourth parcel (D). Zach builds a house on each of the smaller parcels A, B, and C. Zach also builds a road on parcel D. Zach then sells all the parcels. However, the deed conveying parcel D contains a written statement reserving a road easement for each of the parcels A, B, and C. See Ehret v. Gunn (Pennsylvania Supreme Court 1895) |

| 3 | Affirmative appurtenant easement by necessity | Joe owns a large piece of land. He subdivides the land into 2 pieces, one of which is landlocked, and he sells the landlocked parcel to Joe. Joe gets an implied easement by necessity to access the landlocked parcel. |

| 4 | Affirmative appurtenant easement implied by prior use | Sam owns two adjacent rural land parcels in Texas. Parcel #2 is not landlocked as it technically has public road access. However, Parcel #2 has no existing sewer connection, and the public road it can access does not have a sewer line. The closest sewerline Sam could connect Parcel #2 to without crossing any other parcels would require 1 kilometer of new pipe to be laid both on Parcel #2 and alongside the public road. However, if he were to lay a sewer line across Parcel #1, only 100 meters of sewer line would be necessary. Sam decides to take the second approach so he runs the sewer line from Parcel #2 across Parcel #1 to connect to the public main sewerline. A couple years later, Sam sells Parcel #2 to Bob but fails to disclose the sewerline situation or convey any easement for it to Bob. Nevertheless, Bob gets an implied easement by prior use for the sewerline. |

| 5 | Affirmative appurtenant easement by prescription | Fred builds a fence around his property, but he builds the fence 1 foot on his side of the property line. Fred’s neighbor Greg eventually begins storing his trash cans up against the fence on that 1 foot strip. After 5 years, Greg sells his house to a new family who continue the trend of storing trash cans up against the fence. 15 years later, Fred tells the family he is going to rebuild the fence closer to the property line. However, he can’t because the family now holds an affirmative appurtenant easement by prescription, allowing them to continue using that 1 foot strip of land to store trash cans. |

| 6 | Affirmative easement in gross by express grant | Joe owns a beachfront property. His front yard touches the public beach and his backyard touches a public parking lot. Joe sells an easement to Sam, allowing Sam and only Sam to walk over Joe’s property to get back and forth between the parking lot and the beach. Sam now owns an affirmative easement in gross by express grant. |

| 7 | Affirmative easement in gross by express reservation | Joe owns a beachfront property. His front yard touches the public beach and his backyard touches a public parking lot. Joe sells his property to Sam, but in the deed, Joe includes the wording that he “reserves the right to cross the property at any time to get back and forth between the parking lot and the beach”. Joe now owns an affirmative easement in gross by express reservation. |

| 8 | Affirmative easement in gross by necessity | DOES NOT EXIST because easements by necessity are always appurtenant. |

| 9 | Affirmative easement in gross implied by prior use | DOES NOT EXIST because easements by prior use are always appurtenant. |

| 10 | Affirmative easement in gross by prescription | The U.S. Forest Service built and maintained a trail across a piece of property now owned by Wonder Ranch, LLC. The Forest Service built the trail decades ago without permission of the land owner, and the trail has been used openly and notoriously for that entire period. The Forest Service now owns a prescriptive easement for that trail. See Wonder Ranch v. United States (U.S. District Court for Montana 2016) Later affirmed by the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals |

| 11 | Negative easement appurtenant by express grant | A California property owner, Alice, sells a negative easement to her neighbor, Paul, agreeing to never build any structures over 30 feet tall so that Paul’s scenic view will remain unobstructed. Paul now owns a negative easement appurtenant by express grant. |

| 12 | Negative easement appurtenant by express reservation | A California property owner, Paul, owns two adjacent land parcels. Paul sells one of the parcels to Alice, but in the deed, includes a written statement to prohibit Alice or her successors in title from ever building any structures over 30 feet tall so that Paul’s scenic view will remain unobstructed. Paul created (and now owns) a negative easement appurtenant by express reservation in the land parcel he sold to Alice. |

| 13 | Negative easement appurtenant by necessity | DOES NOT EXIST because only affirmative easements can be created by necessity. |

| 14 | Negative easement appurtenant implied by prior use | DOES NOT EXIST because negative easements cannot be implied by prior use. |

| 15 | Negative easement appurtenant by prescription | DOES NOT EXIST because negative easements cannot be created by prescription. |

| 16 | Negative easement in gross by express grant | Bob writes up a deed conveying a conservation easement to a qualified nonprofit organization. The conservation easement restricts the development that can occur on the land. |

| 17 | Negative easement in gross by express reservation | A local government sells a large piece of land, but in the deed, includes a written statement reserving a conservation easement over a large piece of the land. |

| 18 | Negative easement in gross by necessity | DOES NOT EXIST because only affirmative easements can be created by necessity. |

| 19 | Negative easement in gross implied by prior use | DOES NOT EXIST because negative easements cannot be implied by prior use. |

| 20 | Negative easement in gross by prescription | DOES NOT EXIST because negative easements cannot be created by prescription. |

How to avoid the creation of easements by prescription on your property

If you build a fence a few inches within the bounds of your own property (which you should to avoid the fence being classified as a common boundary which must be co-maintained with your neighbor), then you should also send your neighbor an email or other written notice that they have your permission to use that property but that you retain ownership of it and may opt to move the fence and use that property outside the fence at any point in the future. By doing this, you are granting a revocable license to your neighbor to use the property. This prevents the possibility of a prescriptive easement because the usage that leads to a prescriptive easement must be hostile (i.e. not having the permission of the land owner). For good measure, you should also notify anyone new who acquires the neighboring property in case your old neighbor didn’t pass along your message to the new neighbor.

More generally, you can always prevent the creation of a prescriptive easement by granting a revocable license.

However, by taking this approach, you create a new risk: the creation of an easement by estoppel. To eliminate this new risk, you should monitor the licensee’s usage of your property and ensure they do not start investing resources into building infrastructure or improvements to assist their usage. If they do, you should first warn them to stop and then promptly take them to court if they continue.

The 11 ways that easements can be terminated

1. Expiration

Most easements are held in fee simple absolute and they last indefinitely. However, some easements may be created as fee simple determinable easements or life easements (directly analogous to fee simple determinable estates and life estates), in which case they can expire.

It’s also useful to note that personal (as opposed to commercial) easements in gross expire when the easement holder dies.

2. Release

The owner of an appurtenant easement can convey (in writing) the easement to the owner of the servient estate.

A variation of the release termination mechanism is the release/estoppel termination mechanism. In a release/estoppel termination, the owner of the dominant estate only conveys the release of the easement to the owner of the servient estate orally. Normally, this would be invalid under the Statute of Frauds. However, if the owner of the servient estate relies on the oral conveyance, believing it was valid, and subsequently spends $5,000 to re-landscape the part of his property that was used for the easement, then that expenditure acts as estoppel against the easement holder to prevent their use of the easement in the future, in effect, terminating the easement.

3. Prescriptive blockage

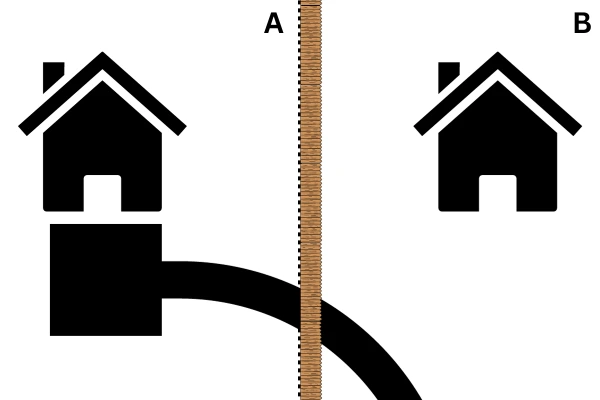

Suppose A has a driveway access easement over B’s land as shown in the illustration below.

Now, suppose B puts up a fence that blocks A’s driveway easement (shown below).

This is illegal, and A can bring a lawsuit to get the fence enjoined by the court. However, if A doesn’t do anything about it for 10-20 years (or whatever the adverse possession period is in A and B’s particular state), then A loses their easement to prescriptive blockage or adverse possession (both terms are used), and the easement ceases to exist.

In principle, the easement would also be terminated if B abandoned his lot and a new, third party C built a fence around B’s lot and eventually acquired it (and the easement) by adverse possession.

Related Cases:

- Spiegel v. Ferraro (Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of NY, 1988)

- Castle Assoc. v. Schwartz (Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of NY, 1978)

4. Merger

Suppose A has a driveway easement over B’s land. If A subsequently sells his land to B, then the easement terminates since both the dominant and servient estates are now owned by the same person, and you can’t own an easement over your own land.

5. Abandonment

You can’t lose an estate by abandonment, but you CAN lose an easement by abandonment. Two facts must be shown to demonstrate abandonment:

- A long period of non-use of the easement (probably a period roughly the same as the adverse possession period)

- Evidence that the easement holder no longer intends to use the easement (e.g. the holder of a driveway access easement over their neighbor’s property builds a wall that blocks off their own driveway or builds a new, more direct driveway that doesn’t use the easement)

6. Cessation of necessity

If and only if an easement is created by necessity, then that easement is automatically terminated upon the cessation of that necessity.

7. Tax sale of the servient land (in some states)

If the servient land is sold in a tax sale, then under common law, any easements on the land would be extinguished. That is the result that prevails in some states, but other states have express statutes that preserve easements through tax sales.

8. Senior mortgage foreclosure on the servient land

If a mortgage was placed on the land before the easement was created, i.e. the mortgage is senior to the easement, and then the mortgage is foreclosed upon, then the easement will be terminated.

9. Condemnation of the servient property under eminent domain

If the government condemns the servient property under eminent domain, then all easements in the servient property are terminated. However, the easement holder may be entitled to compensation.

10. Destruction of the servient property

If someone holds an easement in a building (e.g. a right to use a staircase for access), and subsequently that building is destroyed, then the easement in the building is terminated.

11. Servient land bought by a bona fide purchaser

If a bona fide purchaser buys a piece of land with an easement on it, the easement is terminated as soon as the purchase transaction closes.

A bona fide purchaser is someone who:

- Paid valuable consideration (sometimes interpreted as fair market value) for the property,

- Did NOT have notice (actual or constructive) that the easement existed, and

- Bought the property in good faith (i.e. did not suspect an easement might exist)

NOTE 8: A properly recorded written grant or reservation of easement constitutes constructive notice of an easement. That means properly recorded easements by grant or reservation cannot be terminated by bona fide purchaser.

What is a perpetual easement?

Most easements are “fee simple absolute” easements, which just means that the easement holder holds that easement forever. These easements that last forever are sometimes called perpetual easements.

However, like an estate, it’s also possible for easements to be held in fee simple determinable or for life. Those would be examples of easements which are not perpetual easements.

What is a drainage easement?

A drainage easement is an easement held by a municipality (e.g. a city or local government) for the purpose of channeling rain and storm water. Drainage easements also give municipal governments the right to send workers and equipment onto the easements to maintain and repair them or to install new drainage infrastructure.

Specific rules governing drainage easements usually come from a combination of common law as well as state and local law. However, property owners are frequently not allowed to construct fences, pour concrete, or erect walled structures such as sheds on a drainage easement. For that reason, drainage easements can decrease property values (although they can also help protect properties by decreasing flood risk).

Drainage easements can look like a lot of different things including ditches, storm drains, ponds, culverts, and channels. For example, the image below shows a drainage easement in the front yard of a suburban property.

The next image shows a drainage easement ditch and culvert on a more rural property.

What is a utility easement?

A utility easement is an easement held by a utility company or local government for the purpose of running underground or above ground utilities such as sewer lines, water lines, electrical power lines, natural gas lines, phone lines, or fiber optic cables. Utility easements may also allow the placement of monitoring equipment, electrical poles, or other utility infrastructure. And utility easements always give the easement holder the right to send workers out to maintain, repair, or replace utility equipment.

There are two types of utility easements:

- Utility easements for the specific benefit of the property owner (e.g. an easement for a power line to come to your house to provide you with electrical power), and

- Utility easements NOT for the specific benefit of the property owner (e.g. an easement for a power company to put an electrical pole in your yard and string high voltage power lines across your property for the purpose of supplying power to your whole neighborhood).

States often have statutory law that dictates the rights and responsibilities of both the property owner and the utility company beyond what would be dictated by the common law of easements.

How wide is a utility easement?

The width of a utility easement depends on the type of utility (e.g. water, sewer, electric, natural gas, etc), the size of the property being serviced by the utility (e.g. is it a utility line for a single family home or a 100-unit apartment complex), and the jurisdiction. However, in general, most utility easements are 10 to 30 feet wide.

What is a pipeline easement?

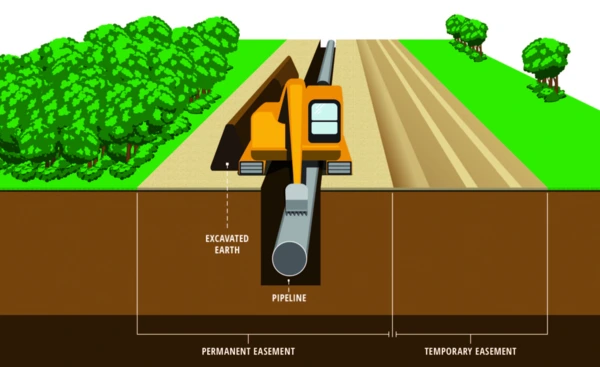

A pipeline easement is an easement for a company (often an oil, gas, carbon credit, or water company) to lay a pipe across your land. Sometimes the pipe may be above ground, but more frequently the pipe will be below the ground.

However, not all pipeline easements are created equally, and many times pipeline companies will bundle a pipeline easement with numerous other easements all under the name “pipeline easement”. A common example of this is a company asking for a permanent easement for a pipeline, plus a temporary easement for construction equipment and materials to be used while the pipeline is being constructed. This example is illustrated below.

Why landowners should carefully read and negotiate any contracts to sell easements to a pipeline company:

- Pipeline construction can make land less agriculturally productive.

- Some pipeline easements also include easements for buildings (usually referred to as surface facilities) to be constructed on the easement in addition to the pipeline.

- Many pipeline easements restrict how a landowner can use the land area of the easement even after the pipeline has been laid. For example, a landowner may not be allowed to grow crops on the easement, or the pipeline company may have the right to simply destroy the crops at your expense if they need to repair or maintain the pipeline.

- A pipeline easement might bisect your property into two pieces that can’t be connected to a single irrigation system.

- Pipeline easements are often bundled with access easements that let the pipeline company drive trucks and equipment over other parts of your land to get back and forth to the easement.

- Pipeline easements are often bundled with contractual agreements that take away landowners’ rights to compensation if the pipeline company does any future damage to your land.

If you are a landowner and have been approached by a pipeline company looking to purchase an easement, you should strongly consider the following recommendations when negotiating the easement:

- Any surface facilities should be specified in writing. If any surface facilities are included, ask for more money from the pipeline company.

- Reserve surface use, and specify examples of allowed and nonallowed uses in writing.

- Any access easements or roads over your non-easement property should be specified explicitly.

- Add damage provisions for extra money in the future. Do not allow the pipeline company to prepay for any future damages at the time they buy the easement.

- Require restoration of the surface land after the pipeline is built.

- Specify any fencing or roads used during construction must be repaired after the pipeline segment across your property is built.

- Do NOT agree to arbitration over future disputes. Retain your right to take the pipeline company to court!

- Require that the pipeline company commit to using the double ditching construction method for laying the pipeline. This will help preserve the value of the land.

If you are approached by a pipeline company who wants to buy an easement from you, negotiate hard because there is a lot at stake. If the company ends up trying to use eminent domain to take an easement by force, then you should hire an eminent domain lawyer (also called a condemnation lawyer). Eminent domain lawyers will typically bill you on a contingency basis, only taking a percentage of any additional settlement money they get you above and beyond what the pipeline company initially offers. That means there is very little to lose by hiring such an attorney, but there is a lot to potentially gain.

What is a driveway easement?

A driveway easement is a vehicular access easement that allows one property owner to drive over the land of a second property owner in order to get to their own property. Some people also use the term driveway easement in a more specific way to mean an easement by necessity for vehicular access to a landlocked parcel.

What is a non-exclusive easement?

An easement can be either exclusive or non-exclusive. An exclusive easement is one which excludes the property owner and/or third parties from using the land area to which the easement applies. Whether the easement excludes use by the property owner, third parties, or both depends on the specific facts of a situation as well as the jurisdiction. For example, in the 2022 case Beggs v. Freed, a Michigan Court of Appeals gave the opinion that an exclusive easement excluded use by both the property owner and third parties. The court acknowledged that this made the easement almost as powerful as “true” ownership of the land area to which the easement applied. The court also said that for that reason, courts do not generally like to interpret easements as “exclusive”.

Exclusive easements are unusual and much less common than non-exclusive easements. Non-exclusive easements are easements which allow the property owner and possibly also third parties to also make use of the land area that an easement applies to, so long as those uses don’t unreasonably interfere with the easement holder’s use.

For example, driveway easements and access easements are almost always non-exclusive easements.

What is a public easement?

A public easement is an easement held by the public. Most public easements are access easements. For example, if people regularly walk across a piece of your land until a dirt path is worn through your grass, and people keep doing that for 20 years without you ever stopping them, then the public might acquire an easement by prescription to continue using that path.

How to value an easement

There are different reasons to value an easement, and the purpose matters when deciding how to assign a dollar value to an easement. Some of the most common reasons why someone would want to value an easement are:

- Land flippers and real estate developers sometimes buy landlocked properties with no access, then negotiate an access easement with the owner of an adjoining land parcel to add value. These deals can be lucrative, or they can fail miserably. The land flipper or developer will often want to estimate the cost of buying the easement ahead of time to ensure the deal makes sense, and the adjoining landowner may want to know the value of the easement they are giving up so they know how much to ask for.

- Utility companies sometimes want to put in new power lines that cross over or under people’s properties. In such cases, the utility company would come to each property owner and try to negotiate the purchase of an easement. Both parties will want to know the value of the easement so they know how much they should pay or ask for. However, since utilities are used for the public, property owners can sometimes be strong-armed by utility companies under the threat of eminent domain. That’s because if the local government really wants to the new utility infrastructure, they can sometimes use eminent domain to forcibly seize an easement from property owners who refuse to willingly sell an easement to the utility company.

- Wealthy individuals sometimes donate conservation easements in order to get tax deductions. In such cases, the easement needs to be valued in order to determine the amount of the deduction allowed by the IRS.

- Oil and gas companies may approach (especially rural) landowners with an offer to purchase an easement to run a pipeline across or under their property. These easement deals can come with complex terms and long-term consequences, so it’s important for landowners to know the value of such easements before they agree to sell one. And lest you think this is all about evil oil and gas companies, clean energy companies do the same thing. There are currently companies buying up easements across America in order to build CO2 pipelines as part of carbon sequestration projects.

- An appraiser, property owner, or property buyer may want to know how much an existing easement will devalue a property relative to similar properties nearby.

Across these various situations, there are 3 general methods to estimate the value of an easement:

- Market exchange value for similar easements sold recently

- Usage value to buyer or seller

- Appraisal delta

Let’s take a deeper look at each.

Market exchange value for similar easements sold recently

If a utility company is running a new powerline through a zip code or a pipeline company is planning to run a pipeline through your county, then you probably aren’t the first person who that utility or pipeline company has approached to buy an easement. Odds are, some people in your community will already have sold easements. If that’s the case, you can look at those examples to see how much people have been getting paid in exchange for the easements and use that to come up with a ballpark estimate of how much you should get paid for an easement.

However, such closely comparable data often isn’t available. For example, if you buy a landlocked parcel of land and want to buy an access easement, there probably aren’t that many similar examples of easements that have been sold in the same community within the last few months or even years. That’s even more true if you plan to do construction on the landlocked parcel because then you need to negotiate not only a permanent access easement for individuals using your property but also a temporary easement to bring in construction equipment and materials to build on the land. In such situations, you may want to try the next method instead.

Usage value to buyer or seller

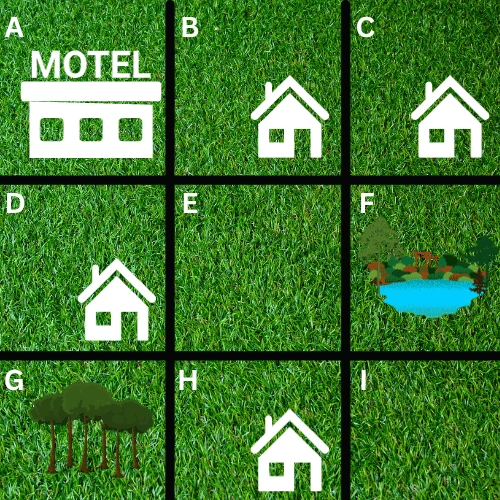

Suppose you are a land flipper, and you come across a landlocked piece of land for sale (shown as parcel E in the diagram below). The black lines are parcel boundaries, and the only roads are along the edges of the image (not shown). Suppose properties B and H recently sold for $300k and $320k, respectively. Parcel E is listed for sale for $30k. There are no easements that have been sold in this community for years. How much would you pay one of the surrounding lots for an easement?

This is actually a very complex question, and the first part of that complexity is knowing what kind of easements you even need. If your plan is to do new construction on parcel E, then you’ll need:

- A permanent access easement to get to and from your property by foot. If there is no street parking, then you probably also need an easement to either park your vehicle on someone else’s property or to drive your vehicle over someone else’s property to get to and from your property.

- A temporary access easement to move construction equipment and materials onto and off of your property in order to construct a building.

- A permanent easement for an electricity line to run to your property.

- A permanent easement for a water line to run to your property.

- A permanent easement for a sewer line to run to your property.

- Possibly a permanent easement for a natural gas line to run to your property.

On the other hand, if you only want to grow a garden on the property, then you may only need the easements for access and water.

Once you know all the easements that you need, you can then consider the value you’re willing to pay. If your plan is to build a new construction house, then based on the comps, you can guess that the final value of the house will be around $300-$320k. If the land costs $30k and you know it will cost $200k to pay someone to construct the house, then your total cost excluding the easement would be $230k. That means you might be willing to pay up to $70k for the easement, but definitely not more.

In reality, that’s an overly simplified analysis that ignores the time value of money and the fact that construction costs over overrun expectations. That means you probably wouldn’t pay more than $10-30k for an easement at most.

Now suppose you are a developer instead of a custom home builder. Assume it costs you the same $200 to build the house. Your total cost excluding the easement is $230k, and you want a roughly 25% gross profit, so you mark that up to $307k. You’re almost smack in the middle of the estimated range you can sell for, based on the available comps, which means you probably won’t pay more than $1k or so for the easements you need. If you can’t buy the easements for that amount, you won’t do the project.

Now consider the seller’s perspective. You are a developer willing to pay $1k for the easements you need. The owner of property A rejects your offer to buy an easement because it will disrupt her motel business to have construction equipment coming through her parking lot. The owners of properties B, C, and D also reject your offer because they don’t want construction equipment coming right next to their houses. The owners of properties F and G reject the $1k offer because you would disturb the outdoor recreation they do on their properties. Property H is owned by a guy who is a little strapped for cash so he accepts your offer. In other words, the final value of the easement was dependent on both the amount the buyer was willing to pay and the specific situation of the seller dictating how much they were willing to take. In simpler terms, the price of an easement depends on how much value it creates for the buyer and how much value it subtracts from the seller.

NOTE 9: If you planned to build a motel instead of a single family property, then you may have been able to mark up construction and land costs to $800k while having an estimated final value of $1M. In that case, you’d have been willing to spend a lot more than $1k on the easement and could have potentially paid enough to get an easement over property D which leads to a better road than the road accessible through property H.

Appraisal delta

The third way to determine how much an easement is worth is to get two appraisals, one which assumes the easement exists and a second which assumes the easement does not exist. Appraisers value property based on its “highest and best use” so this will give you two estimates of how much the property is worth to a hypothetical highest bidder. By subtracting the appraised value of the property without the easement from the appraised value of the property with the easement, you get an estimate of how much the easement itself is worth.

How much is a utility easement worth?

Last week, someone (we’ll call him Bob) emailed me about a builder who contacted him regarding a utility easement. Here’s what Bob said:

“A local builder contacted me yesterday. He bought the field behind my home and said he plans to build three houses back there. However, his only access to the city sewer is through my property. He wants to buy a utility easement from me — about 150 feet, coming down the edge of my land and across the front near the road. He asked me to name a price, but I have no idea where to even start. How much is a utility easement like this worth?”

Firstly, Bob should definitely contact a real estate attorney because easements are a very nuanced area of law, and he would be foolish to sign away any easement without getting a professional legal opinion first.

However, real estate attorneys are not necessarily valuation experts so it’s also useful for Bob to have an idea of how to estimate the value of the easement he is being asked to sell.

In general, Bob can use any of the methods we described in the last section to estimate the value of the easement. Namely, he can use:

- The market exchange value for similar easements sold recently

- Bob’s usage value

- The usage value to the developer

- An appraisal delta

The market exchange value for similar easements sold recently

If you live in a state where real property transactions are recorded with prices (like Florida, but not like Texas), then you can look for other utility easements that have sold in your county and see how much they sold for.

Bob’s usage value

Bob didn’t mention whether or not he was currently using the land that the builder wants an easement on, but that should definitely be considered. For example, if Bob has a garden which would be disrupted by the easement, then he should estimate the value of that garden and not sell the easement for anything less than the value of the garden.

Additionally, the easement is land area that Bob may one day want to build on to expand his house or construct an ADU that he will list on Airbnb. If the easement removes those possibilities, then price of the easement should reflect that. For example, if Bob could spend $60k to construct an ADU on the proposed easement area and that ADU would generate $1,000 per month on average of Airbnb income, then we might value the ADU at $100k. The difference between the $60k construction cost and the $100k final value is the value of the proposed easement land ($50k).

Bob should never agree to sell the easement for less than his own usage value.

The usage value to the developer

If the developer’s cost of land and construction for the three homes is going to be $900k and he anticipates selling the homes for $1.5 million, then he stands to gain $600k if he can obtain the easement. He would definitely not pay $600k, but he might begrudgingly pay $100k if it’s the only way to get the sewer access he needs.

An appraisal delta

Bob could hire an appraiser to do two appraisers, one of the property in its current state and another with the property assuming the easement existed. The difference between the two appraisals is the approximate value of the easement.

However, this requires Bob to pay for two appraisals and is also dependent on knowing exactly where and how big the easement would be. It’s probably not a good idea for Bob to shell out money for appraisers before he even knows if he will make any money from an actual easement sale. For that reason, the previous methods of valuing easements are preferred.

How much is a pipeline easement worth?

In a recent pipeline easement case, a pipeline company approached a farmer wanting to build a pipeline across the farmer’s land. The pipeline company initially offered $50k. The farmer hired an eminent domain lawyer to fight the valuation, and the pipeline company eventually settled for $300k. However, that’s just one case.

The value of a pipeline easement varies widely depending on the location of the land, the length and width of the easement, the usage restrictions of the easement, whether the pipe will be above or below ground, whether any buildings or support structures will be installed above ground next to the pipeline, whether the easement allows vehicular access to the pipeline, whether the easement blocks water flow across the property, whether the easement agreement also includes a prepayment for any potential future damages caused by the construction or operation of the pipeline, and whether or not the pipeline is a common carrier which gives the pipeline company to forcibly seize the easement via eminent domain.

When negotiating a pipeline easement sale, you should always keep three similar questions in mind:

- How much is a pipeline easement worth TO YOU? That is, how much loss of land, agricultural, or other value do you suffer from the easement?

- How much is a pipeline easement worth TO THE MARKET? I.e. what are other nearby land owners selling similar easements for?

- How much is a pipeline easement worth TO THE PIPELINE COMPANY? I.e. what does the pipeline company stand to gain from the pipeline, and what alternatives does the pipeline company have? E.g. could the pipeline company route the pipe around your land? Could they forcibly take an easement with eminent domain? How much would those alternatives cost?

Example:

In Oklahoma, one pipeline company paid some land owners about $1,090 per 100 feet of length of pipeline easement. The same company paid other land owners approximately $4,650 per 100 feet of length of pipeline easement for the same pipeline. The easement in question was 50 feet wide and the differences in price were mostly due to differences in how the land was being used (e.g. residential vs agricultural) as well how well the different landowners negotiated.

How to find easement information on a property

Express easements (by grant or reservation) are recorded at the county recorder’s office or other government office where real estate titles and deeds are tracked. You can find record of such easements through a title search. However, implied easements, easements by necessity, and prescriptive easements are not usually written down anywhere unless a court case has already arisen over them. To identify implied easements, you should ask the current property owner and also inspect the property for signs of third party use (e.g. a dirt trail along the back of the property leading to the neighbor’s yard). To identify a prescriptive easement, you will probably need a surveyor to come out and precisely identify the boundaries of your property so that you can tell if any of your neighbors have been using pieces of your land for a long time (e.g. if your fence is built a foot inside your property line).

Utility easements are usually recorded on subdivision plat maps and/or at the county recorder’s office. Some counties also maintain utility service maps which show utility easements.

Who is responsible for maintaining an easement?

The answer to who is responsible for maintaining an easement depends on both the type of maintenance and the wording of any written agreements used to create or modify the easement. In general, the written agreement creating an express easement can designate either or both parties involved to be responsible for the various aspects of maintenance. However, for express easements that don’t explicitly designate parties responsible for maintenance, as well as for implied and prescriptive easements, the ultimate responsibility for maintenance depends on the type of easement, the type of maintenance, and state law.

For example, Florida common law (e.g. see the case Morrill v. Recreational Development) generally holds that the easement holder rather than the property owner is responsible for maintaining an easement in usable condition. Going further, Florida state statutes even dictate that if an easement is created by necessity without the servient landowner being paid any compensation, then the dominant landowner (the easement holder) is responsible for, at the request of the servient landowner, erecting a gate to keep any livestock on the dominant estate from intruding into the servient estate.

However, the situation can be different if we are talking about responsibility for maintenance to prevent injury rather than responsibility to maintain usability. For example, if the servient property owner invites guests onto the easement and one of those guests is injured by stepping into a pothole on an easement, then the servient property owner may be responsible. On the other hand, if the dominant estate property owner (i.e. the easement holder) invites guests onto the easement, then the dominant property owner will likely be held responsible. And there are still more layers of complexity. If the servient property owner invites guests onto an easement created by necessity without compensation, and a guest is injured by a cow who escapes from the dominant estate because the dominant estate owner has not erected a gate despite being asked to do so by the servient property owner, then the dominant estate owner (the easement holder) may again be responsible under Florida statutes.

Another complicating issue is whether or not an easement is exclusive. If an easement is exclusive, then the dominant property owner almost certainty holds all maintenance responsibility. If the easement is non-exclusive though, then we have to go through all of the analyses previously mentioned to determine who is responsible.

Issues of liability for easement maintenance are unfortunately quite complicated, making it difficult to state general principles. For example, one factor that can play a strong role in determining who is responsible for maintenance in the absence of a written agreement is whether and to what degree each party (servient property owner and easement holder) choose to voluntarily maintain and/or use the easement area. In general, the more use a servient property owner makes of a nonexclusive easement and/or the more the servient property owner voluntarily chooses to maintain the area, the more responsibility for maintenance that owner inherits (again assuming an absence of a written agreement specifying otherwise).

Here is a list of some important factors that come into play when determining who is responsible for easement maintenance:

- Is there a written agreement assigning maintenance responsibilities for an easement? (Although this matters more for purposes of private disputes between servient property owner and easement holder than it does for purposes of liability for third party injuries due to lack of maintenance. See Sutera v. Go Jokir).

- Are there local ordinances or state statutes which govern maintenance responsibilities for easements? This is commonly the case for utility easements and sometimes also for drainage easements and easements by necessity.

- Is the easement exclusive or nonexclusive?

- Does the servient property owner use the easement? If so, how much do they use it?

- Has either the servient property owner or easement holder voluntarily chosen to perform maintenance on the area?

- In the context of a third party injury, what relationship does the third party have to both the servient property owner and the easement holder? Invited licensee? Uninvited licensee? Trespasser?

The table below summarizes some rules of thumb for determining responsible party for nonexclusive easements without a written maintenance agreement.

| Type of Easement | Type of Maintenance Responsibility | Responsible Party |

| Access easement | Maintaining the easement area in a condition that permits the type of usage allowed by the easement | Easement holder |

| Access easement | Not constructing obstacles that block the easement | Property owner |

| Access easement (unused by property owner) | Maintaining the easement area in a safe condition to prevent injury to third parties | Easement holder |

| Access easement (also used by property owner) | Maintaining the easement area in a safe condition to prevent injury to third parties | Property owner (but possibly also easement holder) |

| Drainage easement | Maintaining the easement area in a condition that permits the type of usage allowed by the easement | Easement holder |

| Drainage easement | Maintaining the easement area in a safe condition to prevent injury to third parties | Property owner |

| Utility easement | Maintaining the easement area in a condition that permits the type of usage allowed by the easement | Easement holder |

| Utility easement | Maintaining the easement area in a safe condition to prevent injury to third parties | Easement holder (but possibly also property owner) |

The next table lists some important legal cases that touch on the subject of responsibility for easement maintenance.

| Case | Type of Easement | Method of Easement Creation | Who was Responsible? |

| Petersen v. Friedman (CA 1958) | Negative appurtenant easement preventing view obstruction | Express reservation | Servient property owner was responsible for not obstructing view and for expending effort/resources to remove obstructions they put in place |

| Morrill v. Recreational Development (FL 1982) | Implied appurtenant (statutory) easement by necessity | Implied easement by necessity | The easement holder is responsible for maintaining the easement property area in usable/passable state |

| Collom v. Holton (FL 2nd DCA 1984) | Appurtenant drainage easement | The duty to maintain an easement in a safe condition to prevent injuries to third parties generally rests on the owner of the dominant estate unless (1) there is an agreement requiring the servient owner either solely or concurrently to maintain and control the easement, or (2) the evidence indicates that the servient owner affirmatively and voluntarily otherwise assumed responsibility for maintaining the easement in safe condition as to persons with the same status as the decedents. In this case, the court concluded that it is possible for both the servient property owner and easement owner to be liable for third party injuries on an easement. This finding is consistent with other courts who have found easement holder and property owner jointly liable. | |

| Mills v. City of New York (NY Supreme Court, Special Term, Kings County, 1947) | Appurtenant driveway easement | The servient property owner (the city of New York) was liable for not maintaining a sidewalk so that an injury resulted, despite the relevant section of sidewalk being subject to a driveway easement. | |

| Sutera v. Go Jokir (U.S. Court of Appeals, 2nd Circuit, 1996, NY) | Parking easement | Express grant | Dominant tenement was held responsible for poor maintenance that led to a third party injury despite the existence of a private covenant obligating the servient tenement to maintain the easement area. |

Who is responsible for trees on an easement?

Trees on utility easements for public benefit are usually the responsibility of the utility company. However, as discussed in the previous section, both statutory and case law regarding responsibility for easement maintenance are complex, depending deeply on the facts and circumstances of each specific case as well as jurisdiction.

Can a property owner block an easement?

A property owner is not legally allowed to block an easement because that would constitute unreasonable interference with the right of the easement holder to access and use that land. If a property owner blocks an easement, the easement holder has the right to sue the property owner and obtain an injunction ordering the property owner to remove the blockage, compensate the easement holder, or both.

However, if a property owner believes that the easement holder will not care if the easement is blocked (typically because the easement holder has ceased using it), then the property owner could block the easement. This would still not be legal, and if the property owner is wrong about the easement holder not caring, the easement holder could still take the property owner to court to obtain compensation, an injunction, or both. However, if the property owner is correct, then after waiting for some period of years (usually 5 to 20 years, depending on the state), the easement will cease to exist under the doctrine of adverse possession. Termination of an easement by adverse possession (sometimes also referred to as termination by prescription or termination by prescriptive blockage) is a legally recognized manner of ending an easement, but it is a risky strategy for a land owner to undertake knowingly since it comes with the risk that the easement holder reappears and sues the property owner.

Can a property owner block a utility easement?

A property owner does not have the legal right to block a utility easement. If a property owner does block a utility easement, the utility company has the right to go around the blockage, tear down the blockage, and/or sue the property owner to remove the blockage, depending on the jurisdiction.

Can you build on an easement?

A property owner typically is not allowed to build on an easement if that building would obstruct or hinder the easement holder’s use of the area. However, if an express easement specifies that the property owner is allowed to build certain types of structures on the easement, then the property owner may do so.

What is the difference between an easement and a right of way?

A right of way is a right that one person has to travel over the land of another person. In other words, a right of way is, by definition, an easement for passage. That means all rights of way are easements, but not all easements are rights of way.

However, there is a complication which exists due to common misuse of the terms “easement” and “right of way”. Many people incorrectly use the term easement to refer to a piece of land (which it is not) rather than a right to use that land in a particular way (such as to travel over it, but not live on it or build on it or lease it or sell it). Similarly, people often incorrectly use the term “right of way” to refer to a piece of land rather than just a right to travel over that piece of land. Because of that, people involved in real estate transactions sometimes use the term “right of way” in their contracts without clearly specifying whether they are referring to the land itself or an easement in the land. This is most common when land owners convey land to either local governments or railroad companies. In such situations, the court system may ultimately have to decide whether the transaction was a transfer of land or an easement. That means it is possible for a transaction to involve a right of way but actually (technically) only involve a land transfer, not an easement creation or transfer.

What is the difference between an easement and a profit?

A profit (sometimes called a “profit à prendre) is the right to enter the land of another and to remove timber, minerals, oil, gas, gravel, game, fish, or other physical substances. In other words, it is just like an easement except that it also includes a right to remove something of value from someone else’s land.

It is commonly accepted now that a profit is just a specific type of easement, with the term retained for convenience. That is the position taken, for example, in the “Restatement (Third) of Property: Servitudes”.

What is the difference between a prescriptive easement and adverse possession?

An easement is a non-possessory interest in land. Adverse possession is (as apparent by its name) a possessory interest in land. Both types of interests are acquired from hostile use of someone else’s land, but the type of use that leads to each is different, as summarized in the table below.

| Prescriptive Easement | Adverse Possession | |

| Requirements | A trespasser must use the land in a way that meets the following requirements in order to obtain a prescriptive easement: 1) Use is “hostile“. That just means the user does not have the land owner’s permission. 2) The usage was open and notorious. That means the trespasser was not hiding his usage of the property, and people could easily observe the trespasser using the property. 3) The usage was continuous. What exactly constitutes “continuous” depends on the facts and jurisdiction of the case. | A trespasser must use the land in a way that meets the following requirements in order to obtain title via adverse possession: 1) Use is “hostile“. That just means the user does not have the land owner’s permission. 2) The trespasser must have actual possession of the property. What constitutes “actual” and “possession” depends on jurisdiction and sometimes state statutes, but typically involves some combination of: – Putting up a fence and/or maintaining the property – Improving the property – Paying all property taxes and liens against the property in a timely manner * Occupation is a good indication of possession, but not necessarily actual possession unless additional steps are taken such as performing maintenance and paying property taxes 3) The possession was exclusive (i.e. in the possession of the trespasser alone) 4) The possession was open and notorious. That means the trespasser was not hiding his possession of the property, and people could easily observe the trespasser possessing the property. 5) The possession was continuous. What exactly constitutes “continuous” depends on the facts and jurisdiction of the case. |

| Example of usage that creates the interest | Two neighbors, Bob and Alice, live in a rural area. Bob builds a fence that encroaches on Alice’s property, but Alice doesn’t realize it. Bob stores his garbage cans up against the fence for 20 years. Bob obtains a prescriptive easement to continue using the area against the fence for garbage can storage. | Bob drives past a seemingly abandoned house on the way to work everyday. He looks up the tax records and sees that the owner is behind on property taxes. Bob decides to pay the property tax and move into the house. For the next 20 years, Bob continues to pay the tax and live in and maintain the house. Bob obtains ownership of the house by adverse possession. |

| What the interest allows you to do | Continue to make limited use of the land as you have done in the past. | Make unlimited use of, sell, or lease the land as a true owner could. |

| Florida state law | n/a | F.S. 95.18 – Adverse possession without color of title |

First things to look for when trying to determine if adverse possession or a prescriptive easement applies:

- Has the trespasser been paying property taxes? In a jurisdiction like California, this is necessary for adverse possession but not prescriptive easements.

- Has the trespasser had exclusive use of the land for years? If not, then the trespasser cannot have adverse possession.

Is an easement an encumbrance?

Yes, an easement is an encumbrance on the property in which the easement is held. In the case of an easement appurtenant, the easement is an encumbrance on the servient estate.

Who owns an easement?