“Texans want to own their property, not rent it from the government.”

Texas Governor Abbott

The median Texas property value went up by over 40% during the pandemic, according to Zillow. That means property taxes are also through the roof, and property owners are feeling the burn. Texas legislators have already appropriated $17.6 billion of last year’s nearly $33 billion state budget surplus to help owners with their tax bill. However, Texas Governor Abbott wants to go even further and “make your property tax zero.”

In this article, I’m going to explore the feasibility of that plan and answer several key questions including:

- How big is the Texas government budget?

- Can Texas afford to eliminate property taxes?

- If Texas DID eliminate property taxes, where would the money come from?

- Would school funding be diminished if property taxes were eliminated?

- How high would the sales tax need to be raised to make up the difference, and would that hurt low-income Texans?

Let’s jump in.

How Big is the Texas Government Budget?

The Texas state government spent $127.6 billion in 2022. That includes state dollars spent via programs administered by local governments but does not include local governments spending their own money raised via property taxes, local sales taxes, municipal bond sales, etc.

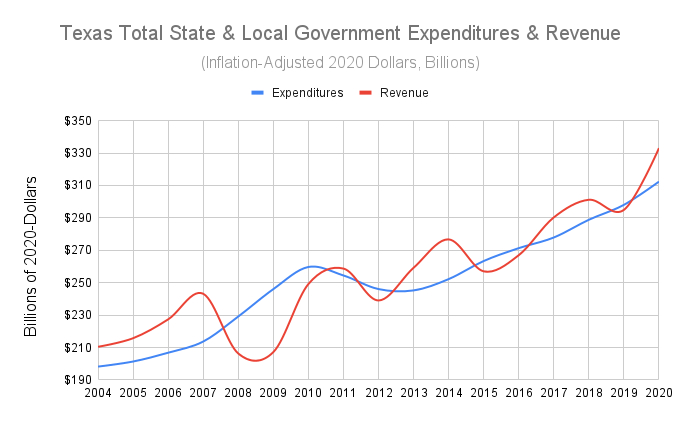

The most recent data I could find on the combined state and local government spending in Texas was from the Tax Policy Center which reported $312 billion of total expenditures and $333 billion of total revenue in 2020.

From the chart above, we can see that both revenue and expenditures have been growing over the last 2 decades. However, from the perspective of a Texas resident, total revenue and expenditures mean very little. Per-capita metrics are much more meaningful, so let’s look at inflation-adjusted state & local revenue per Texas resident:

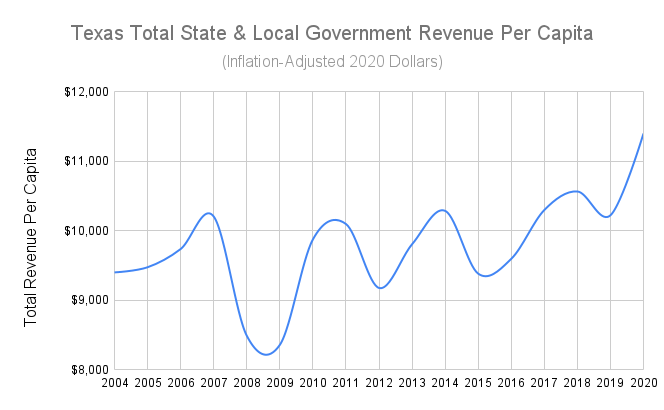

As you can see, real Texas state & local government revenue per capita is trending upwards, but much more slowly than total real revenue (the red line from the last chart). That’s because Texas’ population is growing fast, and that population growth is the primary driver of Texas’ economic growth.

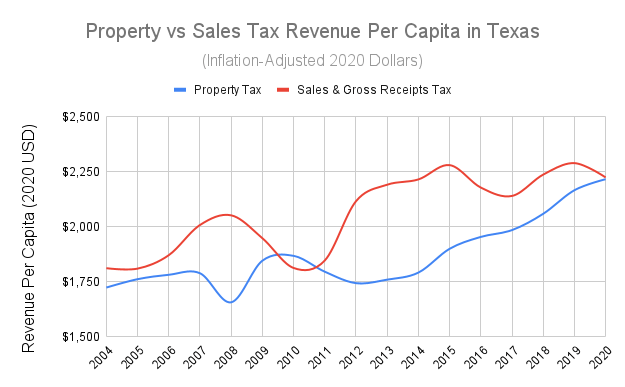

The two most important (from the perspective of Texas residents) contributions to Texas state & local government revenue are property taxes and sales taxes. These two revenue streams are visualized in the next chart.

Like all our charts so far, the chart above is using inflation-adjusted 2020 dollars. That means both property taxes and sales taxes grew faster than inflation for the 16 years from 2004 to 2020. However, property taxes grew the fastest. In 2020, the real cost of property taxes hit an all time high up until that point, whereas the real cost of sales taxes was about the same as it had been 6 years earlier in 2014. And that’s BEFORE the massive run in housing prices from 2020-2022 that far outpaced inflation.

According to Zillow, the median home value in Texas increased from $213,522 in January 2020 to $302,423 in January 2023. That’s a 42% increase! During the same period, total inflation (which drives increases in sales tax revenue) increased only 16%. With that in mind, it’s understandable why many politicians are contemplating lowering property tax rates and increasing sales tax rates.

Can Texas Afford to Eliminate All Property Taxes?

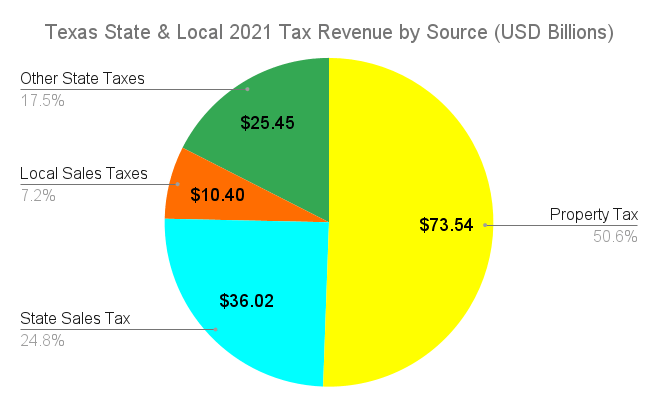

In a word: No. The pie chart below shows the breakdown of Texas’ tax revenue by source. As you can see, property taxes account for over half of all state & local tax revenue in Texas.

Aside: The pie chart above is only for tax revenue, not all revenue. That’s why the numbers add up to much less than the total revenue numbers discussed earlier. Now let’s get back to it.

Fortunately for Texas’ financial stability, nobody is actually suggesting eliminating all property taxes. Governor Abbott may be using that rhetoric (which is, in my opinion, somewhat deceptive), but what he is actually advocating for is an elimination of “M&O” (maintenance and operations) property taxes levied by school districts. In 2021, property taxes levied by school districts accounted for just under 53% of all property taxes collected in Texas, or roughly $39 billion. That’s bigger than the entire $32.7 billion budget surplus Texas’ state government had in 2022. So, how exactly does the Governor plan to eliminate all school district property taxes?

His plan has two parts:

- Use the surplus from last year and future years to pay down property taxes first. The idea is that any surplus would essentially be applied towards reducing property taxes, and only once property taxes were zero would the state legislature be able to allocate additional funding anywhere else.

- Increase the state sales tax.

Initially, the plan would not actually eliminate the property tax but only reduce it by 29%. However, once Texas’ 2022 budget surplus (which was generated from the surge in spending and inflation created by record-high federal Covid stimulus) is spent, it cannot realistically be counted on for future years. That means essentially the entire burden of school funding would fall on the state sales tax.

Currently, the Texas state sales tax rate is 6.25%, with local taxing units having the authority to impose additional sales taxes up to 2%, for a combined maximum rate of 8.25%.

In 2021, the Texas state sales tax generated $36 billion in revenue. That means to generate the $39 billion of additional revenue needed to make the Governor’s plan work, Texas would need to raise the state sales tax rate from 6.25% up to 13.02% (which, after some local jurisdictions added their sales tax, would reach 15.02%).

Except we’re not done. Many places were still shut down in 2021 due to the pandemic which mean consumers spent a record amount on “goods” rather than “services”, and that meant a lot more sales tax revenue than usual.

Additionally, the federal government was still providing stimulus checks to people in 2021 which also boosted consumer spending on physical goods subject to sales tax.

And one more thing. If you double or triple the sales tax, people will naturally buy less stuff. You have to factor that in when estimating how much revenue you’ll generate by hiking the sales tax rate.

If we try to adjust for all of those things, then a more realistic estimate for the necessary state sales tax rate would be 14-15%, which, in some local jurisdictions, would mean a total combined sales tax rate of 16-17%.

Consequences

Raising Texas’ state sales tax from 6.25% to 14.25% would be like having an instantaneous 7% inflation. It would sting (especially for lower income workers), but it wouldn’t necessarily be intolerable. After an initial adjustment period, it would pretty much just be normal. Additionally, Texas does not impose any sales tax on residential rent, groceries, medicine, medical care, or electricity so eliminating property tax in favor of a higher sales tax would not be nearly as unfair to low income Texans as some people are claiming. Rent is the biggest expense for most people, and landlords set the price of rent higher because they need to cover their property taxes. That means eliminating property taxes for landlords would likely slow the growth of rent prices which would actually help low income Texans.

In fact, many low-earning Americans spend over 50% of their income on rent, and the lowest income quartile of Americans spend just over 30% of their income on food. Altogether, low income Texans are quite likely to be spending 90% of their income on goods and services which are not subject to sales tax.

Now let’s run through a quick calculation.

The average effective property tax rate in Texas is 1.60%.

If a renter spends 50% of their income on rent and the rent price goes down by 1.60%, then they save 0.8% of their income.

If the same person also spends 10% of their income on taxable goods and services and the sales tax rate goes up by 7%, then that person pays an extra 0.7% of their income.

Altogether, they are actually saving 0.1% of their income. Of course, this is just one example with lots of baked in assumptions, but it goes to show that swapping a property tax for a higher sales tax isn’t necessary bad for low-income Texans.

Schools

Some educators oppose the Governor’s property tax elimination plan because they want the 2022 budget surplus to go towards education which they say is underfunded in Texas. Let’s see if that’s true.

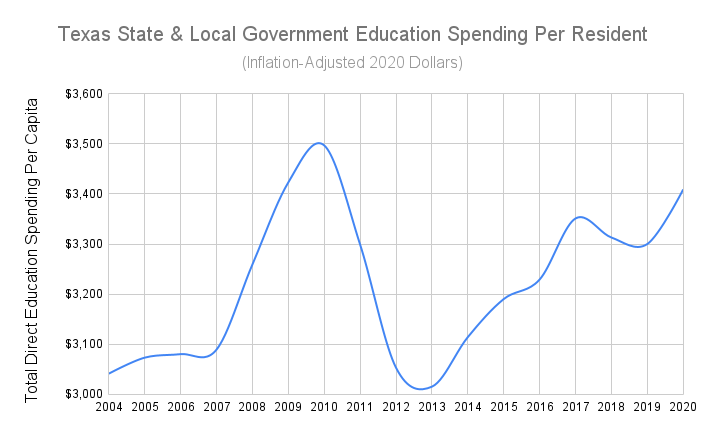

You can always spend more money on education. In a world of trade-offs though, that doesn’t mean you always should. If we look at the graph below of inflation-adjusted government education spending per Texas resident, we see that school funding is not going down. The big bump around 2010 is an artifact of temporary deflation that happened during the financial crisis, but in reality, Texas residents are sending more money than ever towards education.

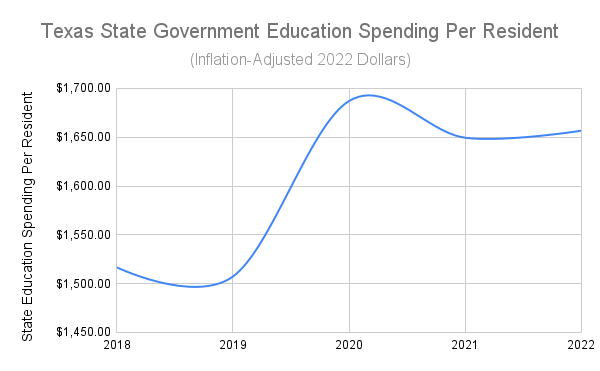

We don’t have access to local government data after 2020, but if we look at just state government data through 2022, we see the same trend continue.

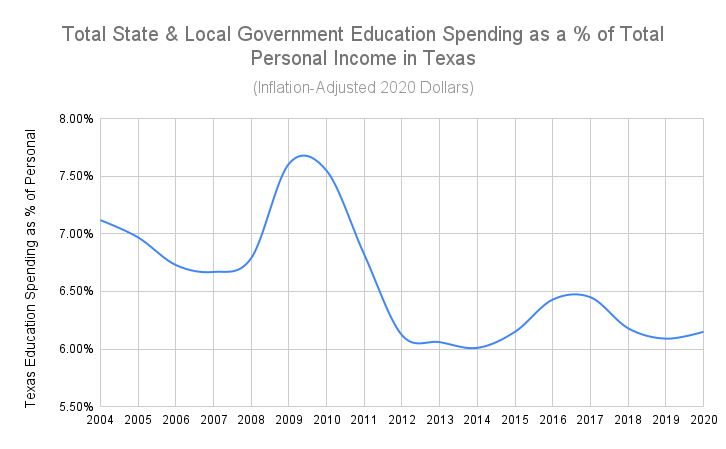

Now let’s look at another chart which shows Texas government education spending as a percentage of total personal income in Texas.

This shows that although Texans are sending more money to government-funded education, they are also making more money due to increased productivity and economic development. This is the ideal situation: People make enough money to keep more and fund schools more. Not everything has to go to schools for a society to prosper.

References

[1] Governor Abbott Vows To Cut Property Taxes At TPPF Fireside Chat

[2] How Do Texas Property Taxes Work?

[3] Tax Policy Center – State & Local Government Finance Data

[4] Texas Comptroller: Revenue & Expenditures Dashboard

[5] Texas Comptroller: Biennial Property Tax Report 2020-2021

What Are “Operating Fund Transfers”?

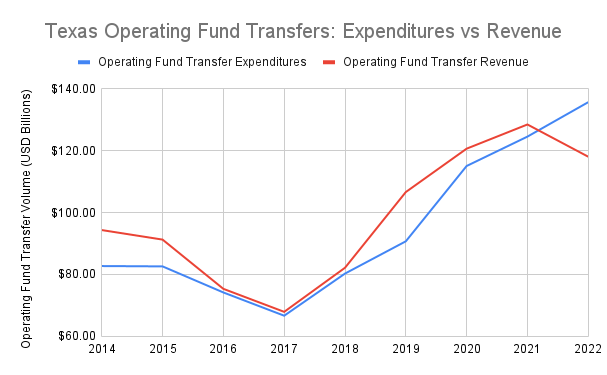

In 2020, the Texas Comptroller reported total revenue of $336.8 billion, including $120.6 billion from “operating fund transfers”. That’s substantially more than Texas’ revenue from federal income ($77.5 billion) or state sales tax ($34.1 billion). In fact, it’s the single largest contribution to Texas’ state revenue by far. So what is an operating fund transfer?

To answer that question, I first need to explain what a “fund” is.

A fund is a bucket of money that is set aside and used for a particular purpose. Funds are used by governments to restrict the uses to which certain cash flows can be used. For example, Texas has the General Revenue Fund (0001) and the Retired School Employee Group Insurance Trust Fund (0989).

An operating fund transfer is a transfer of money from one fund to another. That means that each operating fund transfer shows up as both a contribution to revenue AND as an expense. And if we check Texas’ 2020 budget, we indeed see that operating fund transfers are not only the largest contribution to revenue but also the largest expenditure ($115.0 billion out of $334.4 billion of total expenditures).

But hang on. If each operating fund transfer shows up as both revenue and expense, then how did Texas have $120.6 billion of revenue from operating fund transfers but only $115.0 billion of expenditures from operating fund transfers?

One possibility is that there was a delay between when a transfer was recognized as sent and when it was recognized as received. That hypothesis is supported by the fact that the two numbers are always close, as you can see in the chart below.