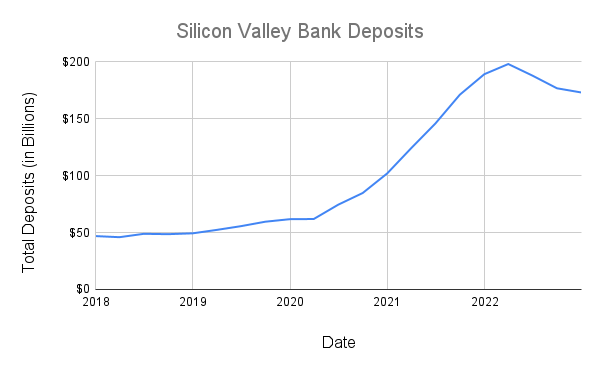

“In 2 years, SVB more than tripled their deposits but couldn’t lend out money as fast as they received it, so they decided to buy over $80 billion in long-term mortgage-backed securities that yielded only 1.56%. The following year, the Fed started hiking interest rates faster than at any other time in the last century.”

On the morning of Friday, March 10, 2023, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was the 16th largest bank in the U.S., serving nearly half of all VC-funded tech and life science companies and 44% of all VC-funded tech & healthcare companies that IPO’d in 2022. Less than 12 hours later, the bank no longer existed, having been shut down by California’s bank regulators and its assets put under the control of the FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation).

SVB’s customers included a lot of big name companies in the tech industry:

- Shopify

- Tableau

- Roblox

- Roku

- ZipRecruiter

- Andreessen Horowitz (VC firm)

- Rippling (payroll company)

- Payoneer (payment company)

- Crowdstrike

- Pivot Energy

- Flow Health (>1,000 employees who weren’t paid on time due to SVB’s failure)

- ~1,000 YC startups

Below is the step-by-step guide on how to blow up a 40 year old bank with lots of prestigious clients.

Step 1: Triple your deposits in two years

On December 31, 2019, SVB had less than $62 billion in total deposits. By December 31, 2021, the bank had over $189 billion in total deposits. That means deposits more than tripled in 2 years.

There are two main reasons for that massive increase in SVB’s deposits during 2020 and 2021.

The first reason is government stimulus during Covid. Stimulus checks and tax credits pumped consumers’ bank accounts full of cash which meant the entire banking system saw a surge in deposits. PPP loans provided an additional burst of deposits to banks that serve businesses and business owners (such as SVB).

The second reason for the surge in deposits is the tech industry boom during the pandemic. The combination of low interest rates, government stimulus money, and the shift to work-from-home culture created a massive boom in both the stock market generally and the tech industry more specifically. Venture capitalists poured money into the bank accounts of private tech startups, and pension funds poured money into the bank accounts of newly minted public tech companies as they IPO’d. Since SVB was the bank for a large number of these companies, it saw a much higher surge in deposits than most banks during that time.

Unfortunately, SVB couldn’t lend out the money as fast as it was receiving new deposits, which is what lead to the second step in destroying a 40 year old bank.

Step 2: Buy $80 billion of bonds yielding 1.56%

Unable to loan out deposits as fast as it wanted, SVB decided to buy over $80 billion of mortgage-backed securities (MBS). 97% of those securities had a 10+ year duration, and the weighted average yield was only 1.56%.

SVB intended to hold those securities until maturity. That was fine at the time because bank accounts were only paying 0.01% interest so SVB still made a lot more money than they spent. The only way things could go wrong is if the bank didn’t hedge its interest rate risk and then the Fed started hiking interest rates.

Step 3: Don’t hedge your risk

SVB’s chief risk officer left in April 2022, and the role went unfilled until January 2023. That means during the highest interest-rate-risk time period in the last 15 years, SVB had no chief risk officer. And it showed. The bank let go of all its interest rate hedges which is completely unheard of for such a large bank.

A bank run is basically a bank getting margin called by its depositors. The reason SVB got margin called is that they essentially took on a HUGE speculative investment position and then let their losses ride for a year without hedging or reducing their position until it was far too late.

Step 4: The Fed hikes interest rates

The Fed hiked interest rates at a faster pace in 2022 than at any other time in history. Higher interest rates dried up VC funding and the IPO markets which meant less money flowing into the bank accounts of the tech companies that used SVB. The huge glut of investment money in 2021 also meant that a lot of bad startups got funded, and once the FOMO of 2020-2021 was over, investors were less enthused with the idea of giving them more cash. That meant dollars started to flow out of tech company bank accounts faster than they flowed back in.

At the same time, higher interest rates dropped the value of SVB’s bond portfolio because of the way bonds are valued.

Together, those two things meant that as tech companies and tech workers kept withdrawing deposits, SVB was forced to sell bonds for less than they bought them in order to get the cash to repay the deposits.

On March 8, 2023, SVB announced they had incurred $1.8 billion of losses on the sale of $21 billion of treasury bonds and that they wanted to raise over $2 billion in fresh money from investors. But instead of giving SVB more money, investors panicked that SVB would also have to sell its MBS portfolio and in the process would incur enough losses that they wouldn’t be able to pay back depositors. So they started pulling money out of the bank as fast as they could. Nobody wanted to buy more stock, and the company’s existing stock price fell 60%.

On March 9th, after failing to raise the money they needed, SVB tried to sell itself to another bank, but companies had already started pulling more money out of the bank in anticipation of problems. In the end, nobody wanted to buy SVB when it had deposits that were quickly evaporating and a bunch of loans that returned 4 times less than treasury bonds.

So, on the afternoon of Friday, March 10, the government stepped in and took over the bank. Unfortunately, only about 7% of the bank’s deposits are covered by FDIC.

That doesn’t automatically mean the other 93% of deposits will just disappear, but it does mean that companies may only get back 80 cents on the dollar, and it may take months to get that money back.

In the meantime, tens of thousands of tech employees weren’t paid, and thousands of companies are now on the brink of failure as they scramble to figure out how to pay their employees and cover expenses while their funds are inaccessible.

Updates

March 12, 2023 at 6:15pm: The Federal Reserve, U.S. Department of the Treasury, and FDIC released a joint statement to designate Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) as a “system risk”. That is important because the FDIC is allowed to fully reimburse all deposits (including uninsured deposits over the normal $250,000 limit) for failed banks that are deemed “systemic risks”, and in the joint statement, the FDIC said explicitly that all SVB depositors would be able to withdraw 100% of their money on Monday, March 13.

Additionally, the joint statement disclosed that New York-based Signature Bank had been shut down by New York regulators, that Signature Bank would also be designated as a “system risk”, and that all Signature Bank depositors would be able to fully withdraw their money on Monday, March 13.

The money to pay depositors of both banks will come from the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) which is funded by fees and assessments on banks, not tax dollars.

Separately, the Federal Reserve also announced a new program called the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) which is designed to prevent other banks from failing for similar reasons to SVB. The BTFP will allow banks (and credit unions) to get cash loans from the Fed by using bonds and other loan assets as collateral. In particular, BTFP allows banks to get loans for the par value of a bond even if the market value of the bond has fallen substantially below the par value due to the rapid rise in interest rates during 2022.

The new program effectively gives banks two years of breathing room because it provides cash loans that are up to 1 year in duration and allows banks to request loans until March 11, 2024. (Technically, the BTFP says “at least” until March 11, 2024, so it’s possible that additional loans may still be used to prop up banks after that.)