State Farm and Farmer’s (the largest and second largest property insurance companies in California) have stopped selling new home insurance policies in the state. And Allstate (the fourth largest property insurance company in California) has limited the number of new home insurance customers it will accept in California. To understand why this is happening, we need to go back in time 17 years.

In 2006, California state lawmakers passed the Global Warming Solutions Act which starts off by stating that “global warming poses a serious threat to the economic well-being, public health, natural resources, and environment of California” with potential adverse impacts that include hotter, drier summers.

Lawmakers used that assessment to justify imposing various fees and taxes on greenhouse gas emitters, but, simultaneously, they kept it illegal for home insurance companies to use climate change models when setting prices for premiums. Instead, insurance carriers that write policies which cover catastrophic fire damage are required to set their prices using a “multi-year, long-term average of catastrophic claims [over] at least 20 years.” They CANNOT base prices on computer climate models that estimate forward-looking wildfire risk.

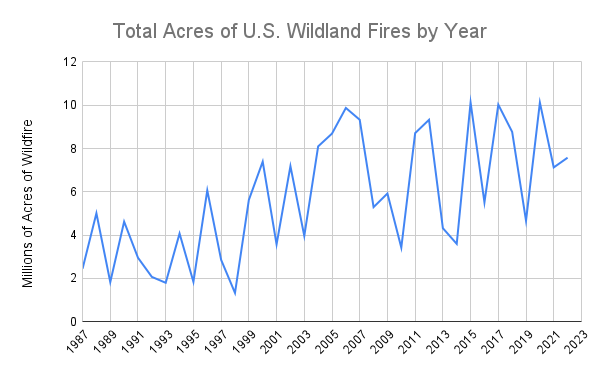

That’s problematic because the climate *is* changing, as evidenced by the steadily increasing number of acres burned by wildfires in the U.S. each year. The number of acres burned by wildfire each year nowadays is roughly 3-4 times what it was in the 1980s.

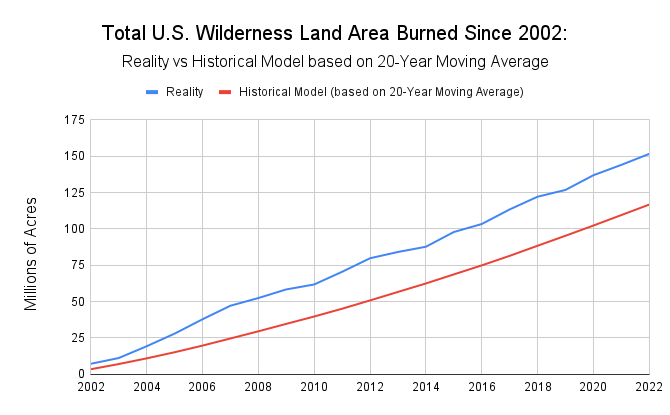

To visualize just how big the gap is between reality and the California Insurance Code, the plot below shows the total (cumulative) acres of U.S. federal wilderness land which have burned in wildfires since the start of 2002 (blue line), and compares it against what the total acres burned should have been if reality matched the 20-year historical moving average that catastrophic insurance prices are required to use (red line).

The blue line above the red line means that wildfires are affecting tens of millions of acres above what would be expected from a historical 20-year average. And that’s just land area. What we really care about is money.

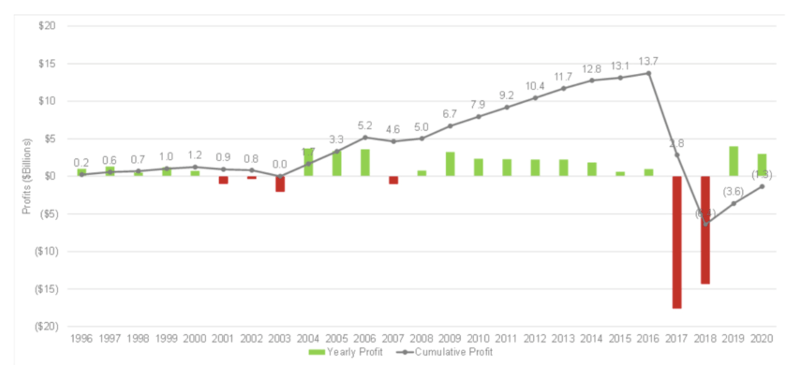

Over two decades of cumulative underwriting profit were wiped out in 2017 and 2018 due in large part to a series of massively destructive fires, including:

- December 2017: Thomas Fire (1,063 structures destroyed, over $2.2 billion in property damage, and over $171 million of losses to the agriculture industry)

- July 2018: Carr Fire (1,604 structures destroyed and more than $1.5 billion in property damage)

- July 2018: Mendocino Complex Fire (280 structures destroyed with over $250 million in total fire-related costs)

- November 2018: Camp Fire (18,804 structures destroyed with over $16.5 billion in property damage)

And that doesn’t even include the most recent data from 2020 and 2021 which had even more intense fire seasons.

- August 2020: August Complex Fire (935 structures destroyed)

- August 2020: SCU Lightning Complex Fire (222 structures destroyed)

- August 2020: LNU Lightning Complex Fire (1,491 structures destroyed)

- August 2020: North Complex Fire (2,455 structures destroyed)

- September 2020: Creek Fire (856 structures destroyed)

- July 2021: River Complex Fire (122 structures destroyed)

- July 2021: Dixie Fire (1,329 structures destroyed and over $1.15 billion in property damage)

State Farm alone recorded an underwriting loss of $13.2 billion in 2022. And yet California’s lawmakers and insurance regulators claim no responsibility for the company pulling out of the state:

“The factors driving State Farm’s decision [to stop writing new policies in California] are beyond our control, including climate change…”

California Department of Insurance statement

You heard that, right? The California Department of Insurance knows that climate change is massively increasing wildfire risk, yet they won’t let insurance carriers price in that risk. It’s ironic, actually. California has one of the highest exposures to increasing climate change risk of any state due to its size and geography, but the California insurance commissioner has barely approved any rate increases in the last decade.

| State | Average Homeowner’s Insurance Premium in 2010 | Average Homeowner’s Insurance Premium in 2018 | 8-Year Change |

| Louisiana | $1546 | $1987 | 28.5% |

| Florida | $1544 | $1960 | 26.9% |

| Texas | $1560 | $1955 | 25.3% |

| Colorado | $926 | $1616 | 74.5% |

| California | $939 | $1073 | 14.3% |

| United States | $909 | $1249 | 37.4% |

As you can see from the table above, the average homeowner’s insurance premium in the U.S. went up by 37.4%, but the average homeowner’s insurance premium in California went up by only 14.3% — about 2.5 times less!

The immediate solution to the insurance crisis is simple, and it’s a solution that the banking industry already adopted years ago in response to the financial crisis: Forward-looking risk estimates.

Like the insurance industry, the banking industry used to estimate credit risk based on historical data. However, after the financial crisis, bank regulators started to think that perhaps banks should be a bit more forward looking in how they estimate credit risk. Bank regulators eventually mandated a new framework called CECL, which stands for Current Expected Credit Losses. CECL is the amount of money a bank expects to lose based not only on historical data but also on future projections that account for possible changes in macroeconomic conditions.

The insurance industry needs something analogous: CEPL (Current Expected Property Losses). California’s insurance regulators need to pass new rules that allow property insurance carriers to set the price of premiums based on forward-looking current expectations of future property losses which might differ from historical trends based on changing climate conditions.

P.S. If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to my free email newsletter to get more like it, and subscribe to my Youtube channel where I cover related topics.

References

[2] The Nature Conservancy & UC Santa Barbara: Long-term trends in wildfire damages in California

[3] Ecology Law Quarterly: California’s ban on climate-informed models for wildfire insurance premiums

[5] California Code of Regulations Title 10, Section 2644.4 — Projected Losses

[6] California Code of Regulations Title 10, Section 2644.5 — Catastrophe Adjustment

- “In those insurance lines and coverages where catastrophes occur, the catastrophic losses of any one accident year in the recorded period are replaced by a loading based on a multi-year, long-term average of catastrophe claims. The number of years over which the average shall be calculated shall be at least 20 years for homeowners multiple peril fire…”

[7] California Code of Regulations Title 10, Section 2644.6 — Loss Development

- “Loss development” is the process by which reported losses are adjusted for anticipated payout patterns. However, loss development data excludes catastrophes.

[8] California Code of Regulations Title 10, Section 2644.6 — Loss and Premium Trend

- California regulations define the terms “loss trend” and “premium trend” both refer to the process by which forces not reflected in historical loss and premium data are expected to affect losses and premiums in the rating period. However, that is a deceptive definition because the “trend” is legally required to exclude catastrophes. So, for example, an increasing frequency of catastrophes due to climate change would not be detected by any “loss trend” or “premium trend”.

[9] California Code of Regulations Title 10, Article 4 – Determination of Reasonable Rates

[10] Biggest insurance companies in California

[11] Property & Casualty Insurance Industry – NAIC 2021 Full Year Report